-

![[Translate to en:] Hilja Hoevenberg an ihrem Schreibtisch im Kriminaltechnischen Institut.](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/1/csm_1920x1080_Hilja-_Hoevenberg_Schreibtisch_c_vdo_e2c098081b.jpg)

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

27.08.2025The Allure of the Unknown

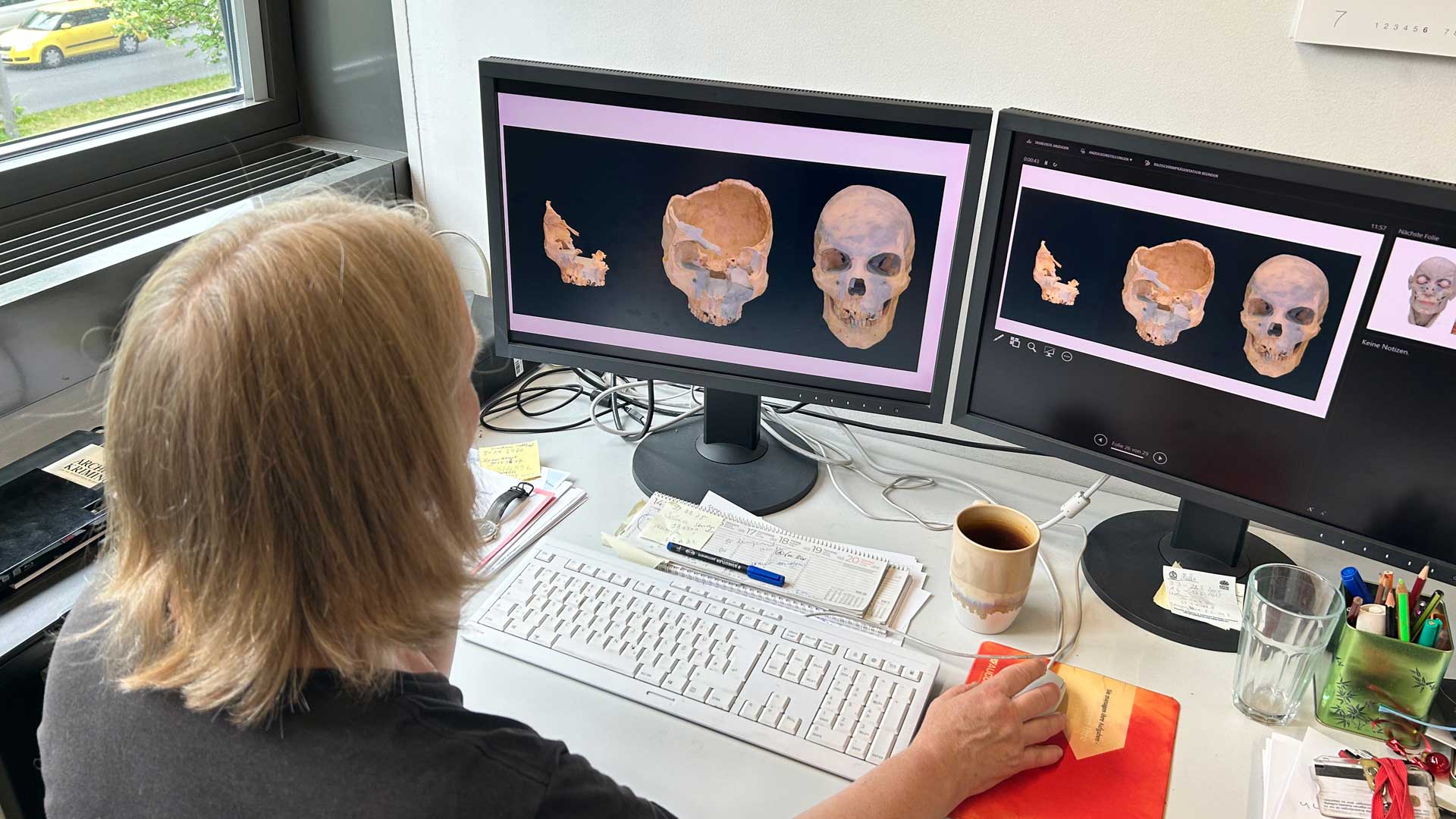

People like Hilja Hoevenberg are usually only known from crime series: As an "Expert in Personal Identification and Facial Soft Tissue Reconstruction" at the Kriminaltechnisches Institut (Forensic Science Institute, KTI) of the Landeskriminalamt Berlin (Berlin Criminal Police Office, LKA), she conducts research in a field that anthropology and anatomy had long abandoned: she reconstructs the faces of unknown victims. In close collaboration with the Institute of Anatomy at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, her work supports not only investigating colleagues but also the victims' relatives.

In November 1988, the half-skeletonized body of a woman was found in the Spandau municipal forest. She lay in a pit that had apparently been disturbed by animals. The body was wrapped in a burlap sack, with two short plastic cords around the neck. The woman had clearly been murdered. How and why she died remains unclear to this day. So does her identity. The Bundeskriminalamt (Federal Criminal Police Office) continues to search for clues: On the website of the international investigation campaign "Identify Me," she is listed as one of 45 unidentified women who were murdered or died under unexplained circumstances. A reconstructed portrait of the Spandau victim is also shown there, accompanied by the note: "A facial soft tissue reconstruction was modeled onto the skull."

In 2025, this "cold case" was reopened. The responsible homicide division requested new examinations from the Kriminaltechnisches Institut of the Landeskriminalamt Berlin, including a new facial reconstruction based on findings from the research project "Correlations between Bone Structures and Soft Tissue in the Head/Neck Region." Hilja Hoevenberg oversees the project at the KTI. Straight blonde hair, black T-shirt, an unadorned face: the "Expert in Personal Identification and Facial Soft Tissue Reconstruction" appears open and highly committed: "Personal identification involves both victims and perpetrators. I compare morphological features using image data to identify individuals," she explains. Hilja Hoevenberg is one of around 470 employees at Germany’s largest forensic science institute. Scientists from fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, biochemistry, psychology, and linguistics support their colleagues in crime scene work and evidence collection. They also conduct interdisciplinary research projects together with technical specialists to develop new solutions and methods for solving and preventing crimes. Their work is internationally networked with authorities, universities, and non-university research institutions. Through her project, Hilja Hoevenberg is affiliated as a guest researcher with the Institute of Functional Anatomy at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, thereby entering a research niche long abandoned by the academic community

Bach and Neanderthals – Early Attempts That Flopped

"The idea of reconstructing soft tissues based on skeletal remains dates back to Georges Cuvier, co-founder of zoology and comparative anatomy. As early as the first half of the 19th century, he proposed supplementing incomplete fossil skeletons and deriving and modeling the associated muscles from bone structures to gain an impression of the type of a particular fossil species," explains Hoevenberg. Cuvier’s idea was taken up by others after 1850. The problem at the time: researchers used metric procedures based on numerical methods and combined the measurements with statistical data analysis techniques. This led to the creation of "typical individual measurements" of various body parts, from which "racial types" or "gender types" were determined based on body surfaces and bones. These average values were also used to identify individuals.

A fascinating example: In 1894, the city of Leipzig commissioned anatomist Wilhelm His to identify the skeleton of a man discovered during expansion work at the Johanniskirche. It was suspected that the remains might belong to composer Johann Sebastian Bach. His prepared a bone report and compared the skull with portrait paintings of Bach, which had only been created after the composer’s death. Based on this, sculptor Carl Ludwig Seffner created a "reproduction of Bach’s features over the skull cast," referencing calculated average values from soft tissue thickness measurements taken from eight healthy elderly male corpses. According to His, the result surpassed "each of the individual portraits in vitality and expressive character" – but it was more of an artistic creation than a scientific reconstruction of the composer’s head. Nevertheless, a review commission concluded from the result that the remains were very likely those of Johann Sebastian Bach.

A similar case involved the "Neanderthal from La Chapelle-aux-Saints": At the beginning of the 20th century, scientists from around the world attempted to reconstruct the face of the prehistoric human based on his fragmented skull, found in France in 1908. The results varied widely. This prompted German anatomist Heinrich von Eggeling to examine the accuracy of facial reconstruction using average soft tissue values. Like many of his scientific contemporaries, von Eggeling ultimately concluded that only the anthropological type could be reconstructed from the skull – not individual facial features. "Around 1930, the door to research on facial soft tissue reconstruction was essentially closed," says Hoevenberg. "The numerical method using average values had proven unsuccessful for reconstructing individual faces."

Back in the Spotlight with Hollywood

The topic lay dormant for a long time. It wasn’t until the release of the U.S. thriller Gorky Park in 1983 that facial reconstruction returned to public attention, sparking renewed interest. In the film, three corpses with disfigured faces are identified through scientific reconstruction. In 1993, Russian anthropologist Natalia Lebedinskaya outlined two unresolved methodological core issues in her Principles of Facial Reconstruction: the correlation between soft tissue and bone structures, and binding rules for determining facial form.

This is precisely where Hilja Hoevenberg’s research begins. Her current project at the KTI was initiated by a real case: “In 2003, a body was found in the harbor of Wittenberge. It could not be identified. My colleagues asked whether I could somehow reconstruct the face. I began with an extensive literature review and then contacted the Institute of Anatomy at Charité to ask whether collaboration within the framework of a master’s thesis would be possible. The then-director, Prof. Dr. Robert Nitsch, was very supportive and enabled me to work systematically on donor bodies. This eventually led to the current research project.”

For four years, Hilja Hoevenberg conducted dissections and searched for correlations between bone structures and soft tissue. Charité gave her the opportunity to attend dissection courses and all lectures relevant to the medical licensing examination. From there, she moved on to formulating rules for determining facial form. “These rules were tested in blind trials and initially not confirmed. I’ve learned to be resilient in the face of disappointment,” she recalls. One of the first key findings of her research: “If you want to reconstruct the head and neck region in a way that represents an individual face, it’s essential to replicate the entire ‘blueprint’ in its individual components. These should then be assembled piece by piece.”

Meticulous Attention to Detail

In her reconstruction work, Hilja Hoevenberg pays close attention to thoroughly examining everything found on and with the body. “As soon as forensic medicine has determined the cause of death, I begin the dissection. I look for morphological information, take notes, and photograph,” she explains. Once the soft tissue has been removed (macerated) from the skull, the reconstruction is built up piece by piece: muscle by muscle, cartilage by cartilage. Fat layers are then applied, followed by the skin. Hoevenberg: “This is modeling compound with tactile properties similar to human skin. The muscles are shaped from wax.” In this phase of her work, the native Dutch woman benefits greatly from her earlier studies in sculpture and painting. “Tactile shape information is also important for human perception: whether something feels soft or hard, appears glossy or matte, rough or smooth. I try to incorporate this into my work as much as possible.” Depending on the case, Hilja Hoevenberg collaborates with dentists or other medical specialists to assess the body for reconstruction.

With her research, Hilja Hoevenberg is a pioneer. Her work not only supports police investigators, but could also be of interest to transplant medicine. She hopes to advance the field further through scientific collective intelligence. Her conclusion: “Interdisciplinary exchange is crucial for research in the field of facial reconstruction.”

Author: Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

-

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Hilja Hoevenberg is conducting research in a field that anthropology and anatomy have long since dismissed. -

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

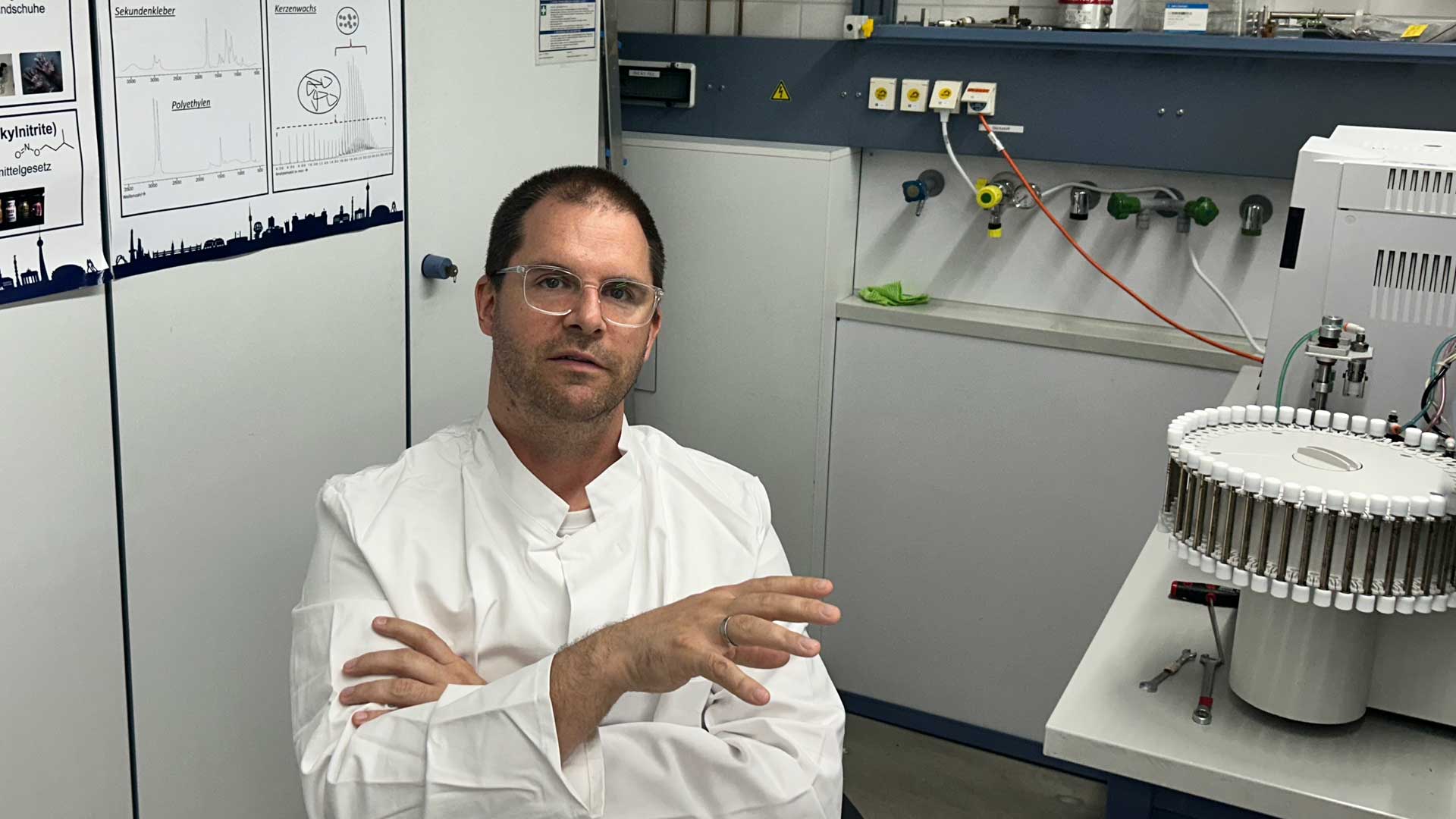

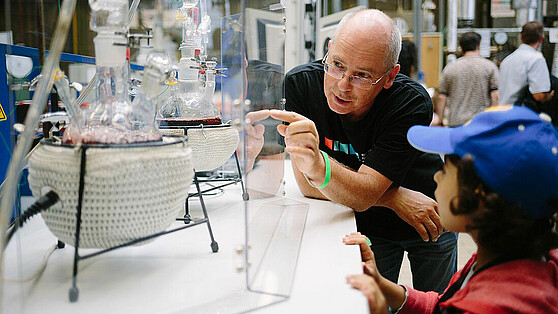

His tasks include analysing traces of gunpowder, paint and break-ins. He also helps uncover forged paintings: Dr Paul Kuhlich heads the Chemistry/Physics Department at KTI. -

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

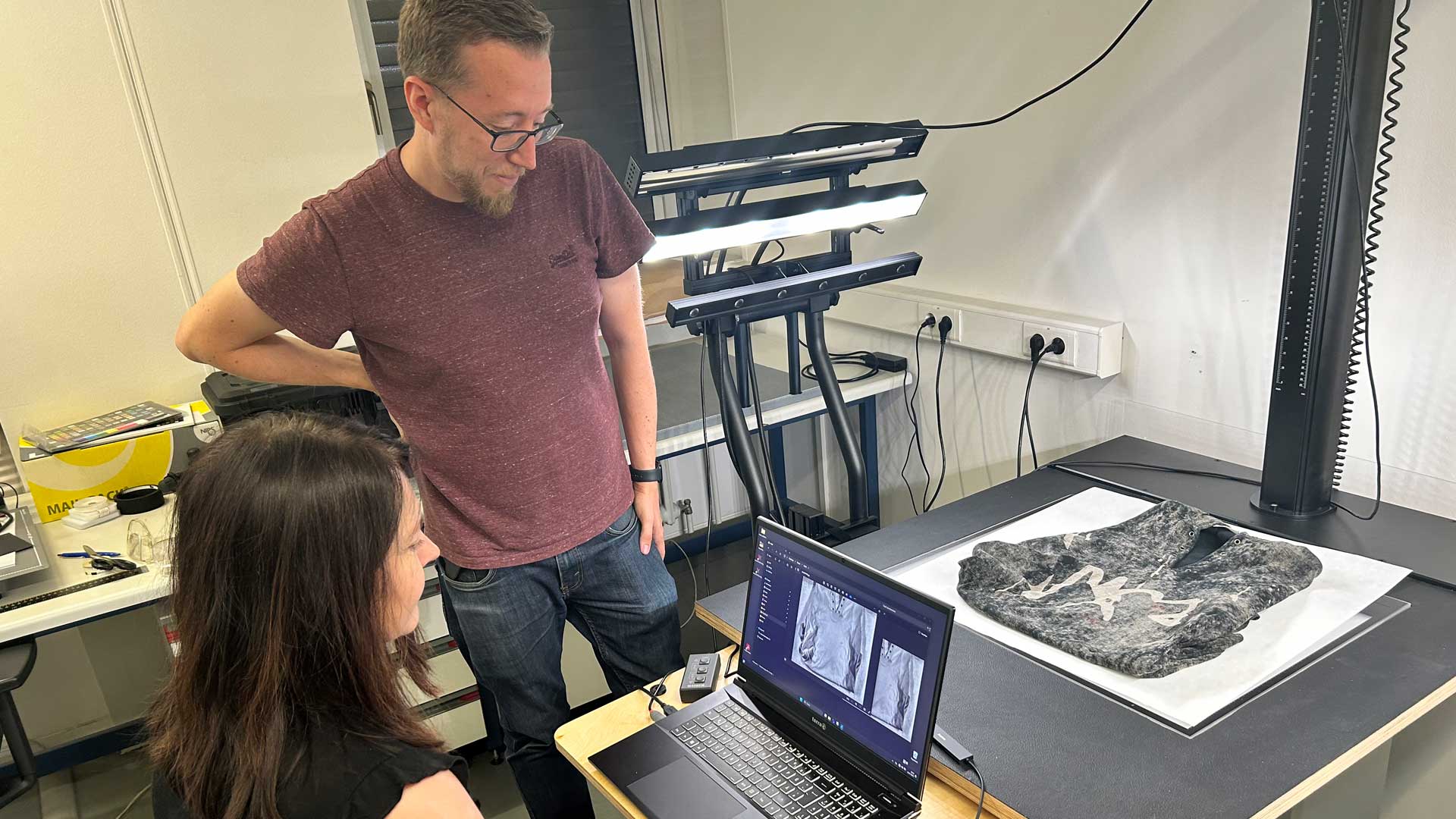

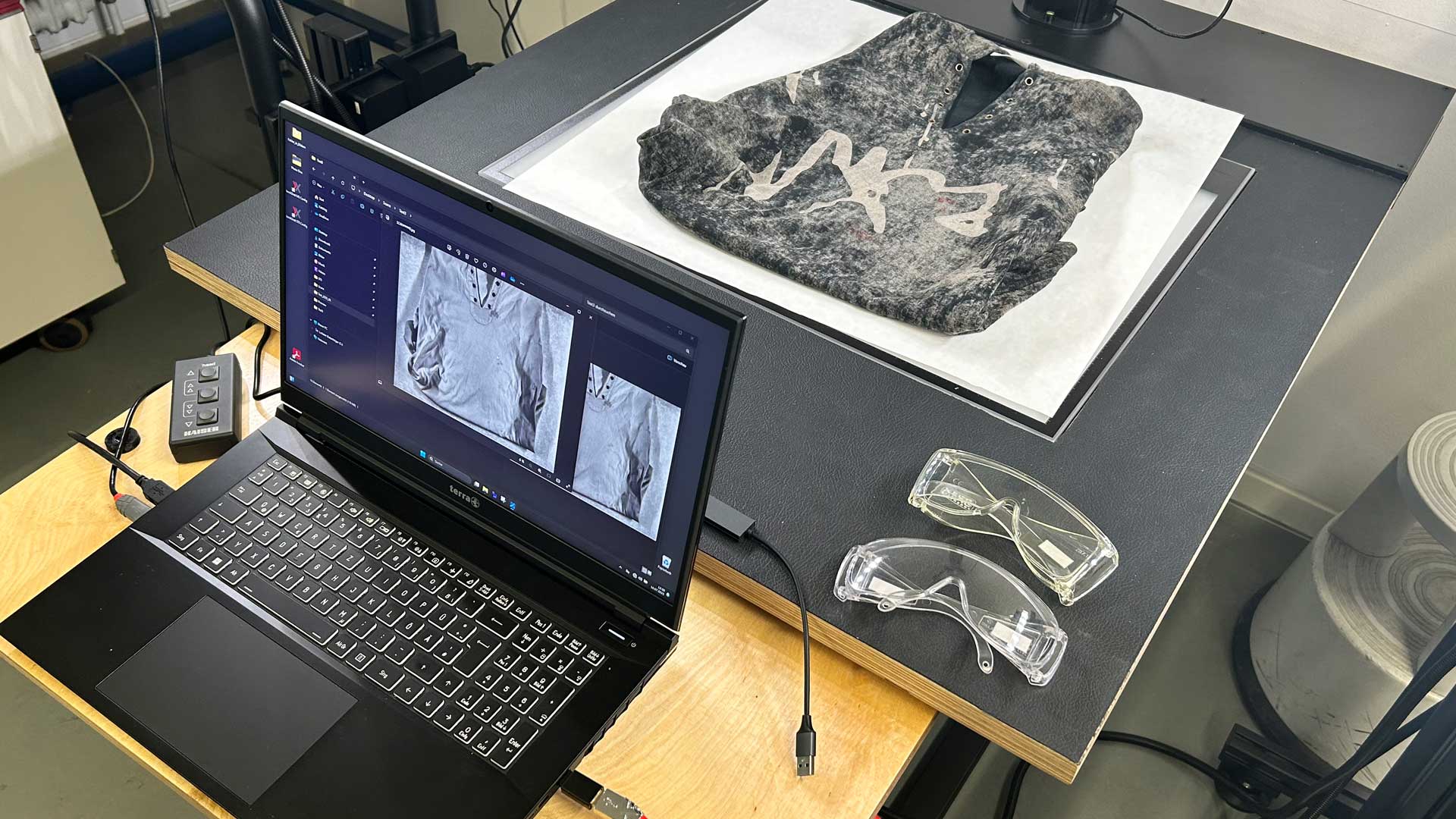

Katja Wild and Tim Skudlarek work as photographers at the KTI. -

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

This multispectral camera allows them to visualise substances that are invisible to the naked eye. For example, traces of blood, semen or paint remnants.

More Information

- #IdentifyMe (the Spandau Case, German only)

- Kriminaltechnisches Institut (LKA KTI) of the Berlin Police

More Stories

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Agentur Medienlabor / Stefan Schubert

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesFive companies from the capital region were honoured for their visionary ideas and products, and another received a special award.→

© Agentur Medienlabor / Stefan Schubert

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesFive companies from the capital region were honoured for their visionary ideas and products, and another received a special award.→Berlin Brandenburg Innovation Award 2025 – The Winners

-

Facts & Events

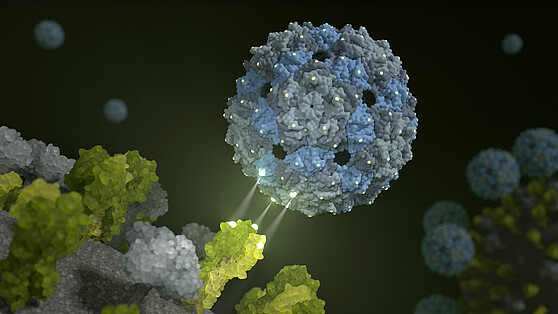

© Berlin University Alliance / Matthias Heyde

Facts & EventsThe decision has been made: Brain City Berlin is entering the next round of Excellence funding from the Federal and State governments with five…→

© Berlin University Alliance / Matthias Heyde

Facts & EventsThe decision has been made: Brain City Berlin is entering the next round of Excellence funding from the Federal and State governments with five…→Excellence strategy: Berlin to participate with 5 clusters

-

Facts & Events

© Graziela Diez

Facts & EventsWith her project "Data Worker's Inquiry", the Berlin-based sociologist and computer scientist draws attention to exploitative conditions in AI labour.…→

© Graziela Diez

Facts & EventsWith her project "Data Worker's Inquiry", the Berlin-based sociologist and computer scientist draws attention to exploitative conditions in AI labour.…→Dr. Milagros Miceli Named to TIME 100 List of the Most Influential People in AI

-

Facts & Events

© Frank Richtersmeier

Facts & EventsAn Easter walk can easily be combined with a good cause. Here are our Citizen Science favourites.→

© Frank Richtersmeier

Facts & EventsAn Easter walk can easily be combined with a good cause. Here are our Citizen Science favourites.→Master Hare and Butterflies – Explore Nature at Easter!

-

Startup Transfer – Stories

© theion

Startup Transfer – StoriesThe start-up theion wants to revolutionise the battery market and accelerate the energy transition with a new technology in Brain City Berlin.→

© theion

Startup Transfer – StoriesThe start-up theion wants to revolutionise the battery market and accelerate the energy transition with a new technology in Brain City Berlin.→“Batteries made in Germany, made in Berlin”

-

Facts & Events

LNDW / Freie Universität Berlin © Rolf Schulten

Facts & EventsWhether it’s about freedom, time or knowledge transfer – the Brain City Berlin calendar of events in 2024 will once again include many exciting topics…→

LNDW / Freie Universität Berlin © Rolf Schulten

Facts & EventsWhether it’s about freedom, time or knowledge transfer – the Brain City Berlin calendar of events in 2024 will once again include many exciting topics…→Brain City Berlin 2024: our Top 10

-

Facts & Events

ThisisEngineering RAEng on Unsplash

Facts & EventsBerlin universities are above the national average in terms of equality. In 2020, the state universities in the Brain City Berlin filled around half…→

ThisisEngineering RAEng on Unsplash

Facts & EventsBerlin universities are above the national average in terms of equality. In 2020, the state universities in the Brain City Berlin filled around half…→Capital of Female Professors

-

Facts & Events

Shutterstock © LightField Studios

Facts & EventsHU Berlin, TU Berlin, ASH Berlin, BHT and HfS Ernst Busch – these Berlin universities have been selected for funding in the first round of the Joint…→

Shutterstock © LightField Studios

Facts & EventsHU Berlin, TU Berlin, ASH Berlin, BHT and HfS Ernst Busch – these Berlin universities have been selected for funding in the first round of the Joint…→Professorinnenprogramm 2030: 5 Berlin universities selected

-

Transfer – Stories

Fotocredit: Ortner & Ortner / Siemens

Transfer – StoriesSiemensstadt 2.0 is a place of the future. The Berlin Senate has approved 9.9 million euros for the first research project "Electrical Drive…→

Fotocredit: Ortner & Ortner / Siemens

Transfer – StoriesSiemensstadt 2.0 is a place of the future. The Berlin Senate has approved 9.9 million euros for the first research project "Electrical Drive…→Siemensstadt 2.0: Research and industry closely linked

-

Facts & Events

SOWG © Sarah Rauch/LOC

Facts & Events#TogetherUnbeatable: The Special Olympics World Games 2023 will be held in the sports metropolis of Berlin from 17 to 25 June. Researchers can…→

SOWG © Sarah Rauch/LOC

Facts & Events#TogetherUnbeatable: The Special Olympics World Games 2023 will be held in the sports metropolis of Berlin from 17 to 25 June. Researchers can…→Special Olympics World Games Berlin: join a researcher!

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Kai Müller Photography

Insights Transfer – StoriesA newspaper interview provided the impetus for founding the start-up. Brain City interview with airpuls founder Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Slawomir…→

© Kai Müller Photography

Insights Transfer – StoriesA newspaper interview provided the impetus for founding the start-up. Brain City interview with airpuls founder Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Slawomir…→airpuls: 5G solutions from research

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Falling Walls Foundation

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesBerlin Science Week is back from November 1 to 10. New this year: The ART & SCIENCE FORUM at Holzmarkt 25 is the central location of the science…→

© Falling Walls Foundation

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesBerlin Science Week is back from November 1 to 10. New this year: The ART & SCIENCE FORUM at Holzmarkt 25 is the central location of the science…→With a focus on art & science: Berlin Science Week 2023

-

Transfer – Stories

Credt: Startup Incubator Berlin

Transfer – StoriesThe Startup Incubator Berlin at the Berlin School of Economics and Law is particularly successful in supporting founder teams – as proved by the fact…→

Credt: Startup Incubator Berlin

Transfer – StoriesThe Startup Incubator Berlin at the Berlin School of Economics and Law is particularly successful in supporting founder teams – as proved by the fact…→“We Bring Ideas to Market”

-

Insights

© WISTA.Plan GmbH / Dirk Laubner

InsightsHow can a quarter such as the Adlershof Science and Technology Park be made climate-resilient and thus future-proof? WISTA Management GmbH is…→

© WISTA.Plan GmbH / Dirk Laubner

InsightsHow can a quarter such as the Adlershof Science and Technology Park be made climate-resilient and thus future-proof? WISTA Management GmbH is…→Blueprint for the Future

-

Transfer – Stories

BHT/Martin Gasch

Transfer – StoriesInterview: Brain City Ambassador Dr-Ing. Ivo Boblan, Professor of the Humanoid Robotics Study Programme at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik, and…→

BHT/Martin Gasch

Transfer – StoriesInterview: Brain City Ambassador Dr-Ing. Ivo Boblan, Professor of the Humanoid Robotics Study Programme at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik, and…→“Robots Can Save us a Great Deal of Work”

-

Transfer – Stories

©Berlin Partner für Wirtschaft und Technologie

Transfer – StoriesMany top-class researchers and scientists are being attracted to Brain City Berlin every year. The Dual Career Network Berlin helps partners of…→

©Berlin Partner für Wirtschaft und Technologie

Transfer – StoriesMany top-class researchers and scientists are being attracted to Brain City Berlin every year. The Dual Career Network Berlin helps partners of…→Dual Career Network Berlin: getting a good start in Berlin

-

Facts & Events

© WZB/David Ausserhofer

Facts & EventsThe political scientist Michael Zürn has been awarded the Berliner Wissenschaftspreis 2021. The Nachwuchspreis went to the theologian Mira Sievers.→

© WZB/David Ausserhofer

Facts & EventsThe political scientist Michael Zürn has been awarded the Berliner Wissenschaftspreis 2021. The Nachwuchspreis went to the theologian Mira Sievers.→Berliner Wissenschaftspreis 2021 for Michael Zürn

-

Transfer – Stories

©Ivar Veermäe / Centre for Entrepreneurship

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Berlin is the German capital of start-ups. Many young companies have successfully been founded through Berlin and Brandenburg based…→

©Ivar Veermäe / Centre for Entrepreneurship

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Berlin is the German capital of start-ups. Many young companies have successfully been founded through Berlin and Brandenburg based…→"Society in particular benefits from high-tech start-ups" - university survey enters its third round

-

Insights Innovations

© Berlin Institute for Innovation

Insights Innovations“Innovation = Invention + Market Penetration” is the working formula of the Berlin Institute for Innovation. The team takes a scientifically sound…→

© Berlin Institute for Innovation

Insights Innovations“Innovation = Invention + Market Penetration” is the working formula of the Berlin Institute for Innovation. The team takes a scientifically sound…→The Research Manufactory

-

Facts & Events

Fotocredit: #MIT Covid-19 Challenge

Facts & EventsApply for the #MIT Hackathon "Beat the Pandemic II" until 26 May! Experts from different fields are sought.→

Fotocredit: #MIT Covid-19 Challenge

Facts & EventsApply for the #MIT Hackathon "Beat the Pandemic II" until 26 May! Experts from different fields are sought.→"Beat the Pandemic II": Join the MIT COVID-19 Challenge

-

Facts & Events

©Agentur Medienlabor/Adam Sevens

Facts & EventsProducts, concepts and solutions are sought that exemplify the innovative capabilities and economic strength of the capital region. Companies based in…→

©Agentur Medienlabor/Adam Sevens

Facts & EventsProducts, concepts and solutions are sought that exemplify the innovative capabilities and economic strength of the capital region. Companies based in…→Berlin Brandenburg Innovation Award 2022: Apply by 4 July

-

Startup

![[Translate to English:] alvaro reyes on unsplash [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/4/csm_alvaro-reyes-unsplash_558x314_4d6fcfac3c.jpg) [Translate to English:] alvaro reyes on unsplash

StartupOb Kniffelspiel oder Sudoku – Gehirntraining gibt es bereits seit Jahrzehnten. Das Berliner Start-up NeuroNation bietet es per Web oder App. Das…→

[Translate to English:] alvaro reyes on unsplash

StartupOb Kniffelspiel oder Sudoku – Gehirntraining gibt es bereits seit Jahrzehnten. Das Berliner Start-up NeuroNation bietet es per Web oder App. Das…→Fitness training for the brain | 21.05.2019

-

Facts & Events

![[Translate to English:] TU Berlin/Dahl [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/1/csm_Freier_Dialog_TU_Berlin_Dahl_558x314_1b3036ca47.jpg) [Translate to English:] TU Berlin/Dahl

Facts & EventsBerlin is one of the most exciting centers for science and research in the world. Brain City Berlin is characterized by international and…→

[Translate to English:] TU Berlin/Dahl

Facts & EventsBerlin is one of the most exciting centers for science and research in the world. Brain City Berlin is characterized by international and…→Brain City Berlin: in free dialog with the world | 13.05.2019

-

shutterstock © Konstantin Yuganov

Keeping an eye on sustainability when shopping online is not easy. The AI-based Green Consumption Assistant is designed to help consumers make…→

shutterstock © Konstantin Yuganov

Keeping an eye on sustainability when shopping online is not easy. The AI-based Green Consumption Assistant is designed to help consumers make…→Green Product Recommendations via AI

-

Facts & Events

Credit: Michael Kompe @ HWR Berlin

Facts & EventsA joint application from five Berlin universities and an individual application bei ASH Berlin for funding under the nationwide "Innovative…→

Credit: Michael Kompe @ HWR Berlin

Facts & EventsA joint application from five Berlin universities and an individual application bei ASH Berlin for funding under the nationwide "Innovative…→“Innovative University” Funding Programme: 2 Berlin Applications Successful

-

Transfer – Stories

© Shutterstock / Studio Romantic

Transfer – StoriesCan elderly people regain independence through targeted exercise? Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Uwe Bettig of ASH Berlin examined this question in…→

© Shutterstock / Studio Romantic

Transfer – StoriesCan elderly people regain independence through targeted exercise? Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Uwe Bettig of ASH Berlin examined this question in…→Fit for home again

-

Transfer – Stories

© Brain City Berlin

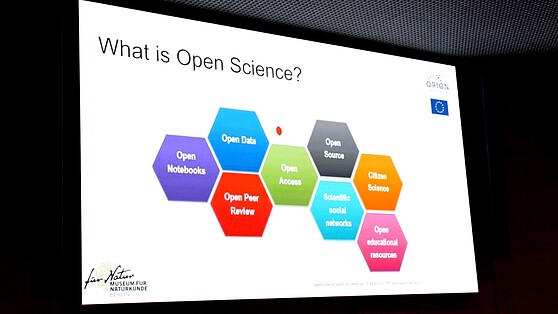

Transfer – StoriesResearch results quickly and easily accessible online: The Open Access movement is campaigning for a paradigm shift in the field of publications and…→

© Brain City Berlin

Transfer – StoriesResearch results quickly and easily accessible online: The Open Access movement is campaigning for a paradigm shift in the field of publications and…→Open Access: free knowledge for everyone

-

Facts & Events

© Landesarchiv Berlin/Wunstorf

Facts & EventsThe linguist was honoured with the Berlin Science Prize 2023 by the Governing Mayor of Berlin, Kai Wegner on May 27. The Young Talent Prize went to…→

© Landesarchiv Berlin/Wunstorf

Facts & EventsThe linguist was honoured with the Berlin Science Prize 2023 by the Governing Mayor of Berlin, Kai Wegner on May 27. The Young Talent Prize went to…→Berlin Science Prize 2023 for Artemis Alexiadou

-

Transfer – Stories

© HTW Berlin / Nikolas Fahlbusch

Transfer – StoriesTeaching is currently only taking place online. Guest author Dr Dorothee Haffner, professor for Museology at HTW Berlin - University of Applied…→

© HTW Berlin / Nikolas Fahlbusch

Transfer – StoriesTeaching is currently only taking place online. Guest author Dr Dorothee Haffner, professor for Museology at HTW Berlin - University of Applied…→Guest contribution: "Online teaching is more engaging than I thought"

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

@ Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Insights Transfer – StoriesListening to sounds like the bat: On "Sound Walk" with Hannes Hoelzl, sound artist and lecturer for Generative Arts/Computational Arts at the UdK…→

@ Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Insights Transfer – StoriesListening to sounds like the bat: On "Sound Walk" with Hannes Hoelzl, sound artist and lecturer for Generative Arts/Computational Arts at the UdK…→Seeing with the Ears

-

Facts & Events

Prof. Claudia Langenberg; Prof. Marlis Dürkop-Leptihn; Prof. Gudrun Erzgräber, der Regierende Bürgermeister Michael Müller und Prof. Gesche Joost (v. li. n. re.), Foto: BIH/Konstantin Börner

Facts & EventsEmmanuelle Charpentier, Lise Meitner, Cécile Vogt – an exhibition in the Rotes Rathaus presents 20 women pioneers from Brain City Berlin – and thereby…→

Prof. Claudia Langenberg; Prof. Marlis Dürkop-Leptihn; Prof. Gudrun Erzgräber, der Regierende Bürgermeister Michael Müller und Prof. Gesche Joost (v. li. n. re.), Foto: BIH/Konstantin Börner

Facts & EventsEmmanuelle Charpentier, Lise Meitner, Cécile Vogt – an exhibition in the Rotes Rathaus presents 20 women pioneers from Brain City Berlin – and thereby…→Exhibition: “Berlin – Capital of Women Scientists”

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Berlin Partner

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe “Additive Manufacturing Berlin Brandenburg” (AMBER) cluster aims to accelerate the transfer of results from cutting-edge research into…→

© Berlin Partner

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe “Additive Manufacturing Berlin Brandenburg” (AMBER) cluster aims to accelerate the transfer of results from cutting-edge research into…→AMBER: Networking cutting-edge research and industry

-

Transfer – Stories

Photo: private

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr. Anna Klippstein, professor of finance and Eliyahu Mätzschker, student at Touro College Berlin.→

Photo: private

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr. Anna Klippstein, professor of finance and Eliyahu Mätzschker, student at Touro College Berlin.→The Pandemic and its Impact on the Capital Market

-

Facts & Events

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/e/csm_University-Ranking_Berlin-Partner_Scholvien_558x314_2e98a4d4aa.jpg) [Translate to English:]

Facts & EventsIn the globally recognized QS University Ranking, Berlin's universities performed very well in many disciplines. They are 30 times among the top 50…→

[Translate to English:]

Facts & EventsIn the globally recognized QS University Ranking, Berlin's universities performed very well in many disciplines. They are 30 times among the top 50…→QS World University Ranking 2019 - Berlin Universities are among the world's best in many disciplines | 21.03.2019

-

Facts & Events

© Berlin University Alliance

Facts & Events“The Open Knowledge Laboratory – for the great transformations of our time”: With a new campaign, the Berlin University Alliance is making…→

© Berlin University Alliance

Facts & Events“The Open Knowledge Laboratory – for the great transformations of our time”: With a new campaign, the Berlin University Alliance is making…→Berlin University Alliance launches a new campaign

-

Facts & Events

© FU Berlin / Svea Pietschmann

Facts & Events"Free thinking. Forming responsibility. Shaping change." Under this motto, the Freie Universität Berlin is celebrating its 75th birthday this year…→

© FU Berlin / Svea Pietschmann

Facts & Events"Free thinking. Forming responsibility. Shaping change." Under this motto, the Freie Universität Berlin is celebrating its 75th birthday this year…→75 Years of Freie Universität Berlin

-

Innovations

![[Translate to English:] Shutterstock/ Jacob Lund [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/4/csm_shutterstock_jacob_lund_588x314_75e5e9bf67.jpg) [Translate to English:] Shutterstock/ Jacob Lund

InnovationsThe capital city fills almost half of the professorships with female scientists: 48 percent of the calls for professorships made by Berlin…→

[Translate to English:] Shutterstock/ Jacob Lund

InnovationsThe capital city fills almost half of the professorships with female scientists: 48 percent of the calls for professorships made by Berlin…→Brain City Berlin – pioneering in equality issues | 10.07.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

©BIH|Thomas Rafalzyk

Transfer – StoriesAt the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) the main focus is on "translational research" - the transfer of findings from the research lab into clinical…→

©BIH|Thomas Rafalzyk

Transfer – StoriesAt the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) the main focus is on "translational research" - the transfer of findings from the research lab into clinical…→“There are now many great female scientists, achieving great things”

-

Facts & Events

Prof. Dr. Volker Haucke: FMP © Silke Oßwald; Prof. Dr. Ana Prombo: MDC © Pablo Castagnola

Facts & EventsProf. Dr. Ana Pombo (MDC) and Prof. Dr. Volker Haucke (FMP), have been awarded the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize 2025.→

Prof. Dr. Volker Haucke: FMP © Silke Oßwald; Prof. Dr. Ana Prombo: MDC © Pablo Castagnola

Facts & EventsProf. Dr. Ana Pombo (MDC) and Prof. Dr. Volker Haucke (FMP), have been awarded the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize 2025.→Leibniz Prize for 2 top Berlin researchers

-

Transfer – Stories

Credit: Rudolf Grillborzer

Transfer – StoriesGuest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr.-Ing. Onur Günlü, Technische Universität Berlin.→

Credit: Rudolf Grillborzer

Transfer – StoriesGuest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr.-Ing. Onur Günlü, Technische Universität Berlin.→Exploring the "ultimate limits"

-

Facts & Events

left: TU Berlin, Pressestelle / right: Marten Körner

Facts & EventsSeveral researchers in Brain City Berlin have recently received top-class prize grants. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prizes were awarded to Prof. Dr…→

left: TU Berlin, Pressestelle / right: Marten Körner

Facts & EventsSeveral researchers in Brain City Berlin have recently received top-class prize grants. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prizes were awarded to Prof. Dr…→7 research awards for Berlin scientists

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© ASH Berlin/Cristián Pérez

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe acronym SAGE, in German stands for Social Work, Health, Education and Training. Prof. Bettina Völter, Rector at the ASH Berlin, tells us more…→

© ASH Berlin/Cristián Pérez

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe acronym SAGE, in German stands for Social Work, Health, Education and Training. Prof. Bettina Völter, Rector at the ASH Berlin, tells us more…→SAGE – a social three-way alliance

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

Shutterstock © optimarc

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith a new transfer certificate, the TU Berlin certifies practical skills for students who have dealt with methods and issues of knowledge and…→

Shutterstock © optimarc

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith a new transfer certificate, the TU Berlin certifies practical skills for students who have dealt with methods and issues of knowledge and…→Thinking outside the box

-

Transfer – Stories

Credit: André Bakker

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr Anabel Ternès von Hattburg, Professor for International Business Administration at the SRH…→

Credit: André Bakker

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr Anabel Ternès von Hattburg, Professor for International Business Administration at the SRH…→Getting on Board with Digitality

-

Facts & Events

![© LNDW [Translate to en:] Motiv LNDW 2025, Brain City Berlin](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/5/csm_1920x1080_lndw25_neutral-2_c79195d6c2.jpg) © LNDW

Facts & EventsThe LNDW is celebrating its anniversary this year. The programme includes more than 1,000 events. Tickets are available at a special anniversary…→

© LNDW

Facts & EventsThe LNDW is celebrating its anniversary this year. The programme includes more than 1,000 events. Tickets are available at a special anniversary…→25 years of Long Night of Science

-

Insights

© Neurospace

InsightsThe start-up Neurospace stands like no other for the booming “New Space” industry in Brain City Berlin. An interview with Irene Selvanathan, founder…→

© Neurospace

InsightsThe start-up Neurospace stands like no other for the booming “New Space” industry in Brain City Berlin. An interview with Irene Selvanathan, founder…→“We want to take science and industry to the moon”

-

©Wolf Lux

Brain City interview with Ramona Pop, Mayor of Berlin and Senator for Economics, Energy and Public Enterprises.→

©Wolf Lux

Brain City interview with Ramona Pop, Mayor of Berlin and Senator for Economics, Energy and Public Enterprises.→

"Berlin is a city of innovation"

-

Transfer – Stories

©Matthias Picket

Transfer – StoriesDr. Anne Schreiter, Managing Director of the German Scholars Organization (GSO), reveals in the Brain City interview what alternative career…→

©Matthias Picket

Transfer – StoriesDr. Anne Schreiter, Managing Director of the German Scholars Organization (GSO), reveals in the Brain City interview what alternative career…→"Science is not just about research"

-

Facts & Events

© Terrartives, Crete, Greece

Facts & EventsClimate protection where others go on holiday: How Berlin-based research is making the Mediterranean more resilient→

© Terrartives, Crete, Greece

Facts & EventsClimate protection where others go on holiday: How Berlin-based research is making the Mediterranean more resilient→Climate protection where others go on holiday: How Berlin-based research is making the Mediterranean more resilient

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© HWR Berlin/ Franziska Ihle

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the project “KlinKe”, Prof. Dr. Silke Bustamante and her colleague Prof. Dr. Andrea Pelzeter at the HWR Berlin are researching which of the…→

© HWR Berlin/ Franziska Ihle

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the project “KlinKe”, Prof. Dr. Silke Bustamante and her colleague Prof. Dr. Andrea Pelzeter at the HWR Berlin are researching which of the…→On the way to becoming a climate-neutral hospital

-

Transfer – Stories

© Pocky Lee on Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesMatches in front of empty stadiums, virtual marathons, and many postponed events. Brain City Ambassador Professor Gabriele Mielke is tracking the…→

© Pocky Lee on Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesMatches in front of empty stadiums, virtual marathons, and many postponed events. Brain City Ambassador Professor Gabriele Mielke is tracking the…→"Now is the time for innovators"

-

Facts & Events

© FU Berlin/Bernd Wannenmacher

Facts & Events“Oral-History.Digital” is the name of a portal that went online this week. The University Library of the FU Berlin is a partner in the project funded…→

© FU Berlin/Bernd Wannenmacher

Facts & Events“Oral-History.Digital” is the name of a portal that went online this week. The University Library of the FU Berlin is a partner in the project funded…→New platform for contemporary witness interviews

-

Facts & Events

![[Translate to English:] ©Marcel/Unsplash [Translate to English:] Fledermaus Grafiti](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/a/csm_1920x1080-fledermaus-marcel-unsplash_1ee08293c8.jpg) [Translate to English:] ©Marcel/Unsplash

Facts & EventsBe it the greater mouse-eared bat, the brown long-eared bat, the serotine bat or the common noctule – bats feel particularly at home in Berlin. 18 of…→

[Translate to English:] ©Marcel/Unsplash

Facts & EventsBe it the greater mouse-eared bat, the brown long-eared bat, the serotine bat or the common noctule – bats feel particularly at home in Berlin. 18 of…→Until 8th of March: Bat Capital seeks hobby researchers

-

Facts & Events

©Berlin Science Week 2019

Facts & Events23.10.2019 | Over 350 top researchers from all over the world, more than 130 events, and a new format: the "Berlin Science Campus". Berlin Science…→

©Berlin Science Week 2019

Facts & Events23.10.2019 | Over 350 top researchers from all over the world, more than 130 events, and a new format: the "Berlin Science Campus". Berlin Science…→10 days dedicated to science: Berlin Science Week 2019

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

CCC © Michael Reinhardt

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview with Dr. Anita Dame, Managing Director of the Climate Change Center Berlin Brandenburg.→

CCC © Michael Reinhardt

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview with Dr. Anita Dame, Managing Director of the Climate Change Center Berlin Brandenburg.→“Climate transformation is a marathon”

-

Facts & Events

© Ilja C Hendel / Wissenschaft im Dialog, CC BY-SA 4.0

Facts & EventsIt's that time again: the exhibition ship once again is sailing on German waters. 29 cities are on the programme this year.→

© Ilja C Hendel / Wissenschaft im Dialog, CC BY-SA 4.0

Facts & EventsIt's that time again: the exhibition ship once again is sailing on German waters. 29 cities are on the programme this year.→Ahoi! MS Wissenschaft on Tour 2025

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Hallbauer & Fioretti

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview: Prof. Dr. Emmanuelle Charpentier, Nobel Laureate and Managing Director of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens.→

© Hallbauer & Fioretti

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview: Prof. Dr. Emmanuelle Charpentier, Nobel Laureate and Managing Director of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens.→"Basic research is the basis for innovation"

-

Facts & Events

© Agentur Medienlabor

Facts & EventsThe application phase is open: Until July 8, companies, start-ups and craft businesses based in the Capital Region can submit their documents for the…→

© Agentur Medienlabor

Facts & EventsThe application phase is open: Until July 8, companies, start-ups and craft businesses based in the Capital Region can submit their documents for the…→Starting signal for the Berlin Brandenburg Innovation Award 2024

-

Facts & Events

©Marvin Meyer/Unsplash

Facts & EventsMore students than ever before are expected to be enrolled at the colleges and universities in the Brain City Berlin by the winter semester 2019/20.…→

©Marvin Meyer/Unsplash

Facts & EventsMore students than ever before are expected to be enrolled at the colleges and universities in the Brain City Berlin by the winter semester 2019/20.…→Start of the semester: 195,000 students expected | 17.10.2019

-

Startup Transfer – Stories

© STOFF2/Kerstin Reisch

Startup Transfer – StoriesBerlin Start-up STOFF2 wants to bring the ‘Zinc Intermediate-step Electrolyser’ (ZZE) to market maturity and is working closely with the TU Berlin to…→

© STOFF2/Kerstin Reisch

Startup Transfer – StoriesBerlin Start-up STOFF2 wants to bring the ‘Zinc Intermediate-step Electrolyser’ (ZZE) to market maturity and is working closely with the TU Berlin to…→The small, subtle intermediate step

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_helena-lopes-1338810-unsplash_558x314_857802ad2f.jpg) [Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesSend a digital lollipop or delicate fragrance notes via email or let the wind virtually blow against your face - research makes it possible. Learn…→

[Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesSend a digital lollipop or delicate fragrance notes via email or let the wind virtually blow against your face - research makes it possible. Learn…→Experiencing the digital world with all senses | 18.06.2019

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© HTW/ZfS

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesClimate, health and sustainability – these are the main topics of Transferale. From 25 to 27 September, the science and transfer festival will be held…→

© HTW/ZfS

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesClimate, health and sustainability – these are the main topics of Transferale. From 25 to 27 September, the science and transfer festival will be held…→Ideas for Berlin’s future

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Gorodenkoff / Shutterstock.com

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview: Prof. Dr. Petra Ritter gives an insight into the cross-border project TEF-Health.→

© Gorodenkoff / Shutterstock.com

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview: Prof. Dr. Petra Ritter gives an insight into the cross-border project TEF-Health.→European test infrastructure for AI in healthcare

-

Insights Facts & Events

© Matters of Activity / HU Berlin

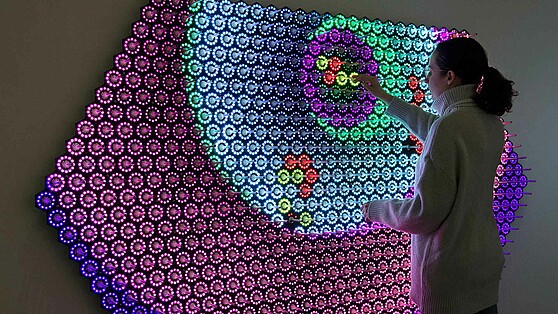

Insights Facts & EventsOn 19 September, the Cluster of Excellence ‘Matters of Activity’ will hold its final annual conference. Brain City interview with Dr Christian Stein.→

© Matters of Activity / HU Berlin

Insights Facts & EventsOn 19 September, the Cluster of Excellence ‘Matters of Activity’ will hold its final annual conference. Brain City interview with Dr Christian Stein.→“We bring the material to eye level”

-

Facts & Events

shutterstock.com©NicoEINino

Facts & EventsIn the "OpinionGPT" project, researchers at HU Berlin are investigating how biased training data affect artificial intelligence responses.→

shutterstock.com©NicoEINino

Facts & EventsIn the "OpinionGPT" project, researchers at HU Berlin are investigating how biased training data affect artificial intelligence responses.→Deliberately biased

-

Facts & Events

Image: Berlin University Alliance

Facts & Events"Wissen aus Berlin" (Knowledge from Berlin) is the name of a YouTube channel of the Berlin University Alliance. There is a new episode every Tuesday.→

Image: Berlin University Alliance

Facts & Events"Wissen aus Berlin" (Knowledge from Berlin) is the name of a YouTube channel of the Berlin University Alliance. There is a new episode every Tuesday.→Knowledge from Berlin

-

Facts & Events

© Christop Sapp (denXte)

Facts & EventsProf. Dr. Barbara Vetter from the FU Berlin and Prof. Dr. Klaus-Robert Müller from the TU Berlin receive Germany's most prestigious research funding…→

© Christop Sapp (denXte)

Facts & EventsProf. Dr. Barbara Vetter from the FU Berlin and Prof. Dr. Klaus-Robert Müller from the TU Berlin receive Germany's most prestigious research funding…→Leibniz Prizes for Philosopher and Computer Scientist from Berlin

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Alfred-Wegener-Institut/Micheal Gutsche (CC-BY 4.0)

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesA special exhibition at the Deutsches Technikmuseum makes things crystal clear: There is little time left to save the Arctic.→

© Alfred-Wegener-Institut/Micheal Gutsche (CC-BY 4.0)

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesA special exhibition at the Deutsches Technikmuseum makes things crystal clear: There is little time left to save the Arctic.→Exhibition tip: “Thin ice”

-

Facts & Events

UVB 2019 / André Wagenzik

Facts & EventsBrain City Berlin is considered one of the leading locations in Germany working on artificial intelligence. Berlin science is an important driver of…→

UVB 2019 / André Wagenzik

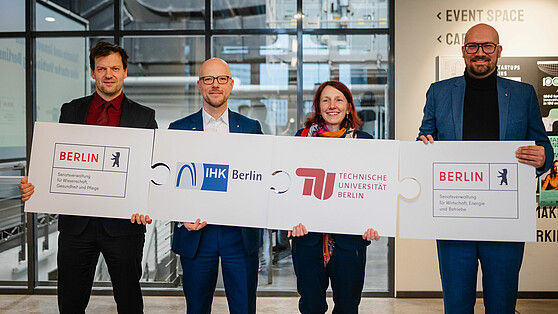

Facts & EventsBrain City Berlin is considered one of the leading locations in Germany working on artificial intelligence. Berlin science is an important driver of…→Accelerating the digital transformation: TU Berlin and business associations intensify cooperation | 02.10.2019

-

Facts & Events

© Futurium/Ali Ghandtschi

Facts & EventsFor all those who have not yet planned anything specific for the weekend - here are a few tips from the Brain City editorial team combining leisure…→

© Futurium/Ali Ghandtschi

Facts & EventsFor all those who have not yet planned anything specific for the weekend - here are a few tips from the Brain City editorial team combining leisure…→5 tips: Weekend in Brain City Berlin

-

Facts & Events

© xg-incubator.com

Facts & EventsUntil March 31, start-ups and founders can apply for the new xG-Incubator of TU Berlin and Fraunhofer HHI.→

© xg-incubator.com

Facts & EventsUntil March 31, start-ups and founders can apply for the new xG-Incubator of TU Berlin and Fraunhofer HHI.→Apply now! Ideas for the future of communication

-

Facts & Events

© Beuth Hochschule / Karsten Flügel

Facts & EventsBuildings, lecture halls and laboratories in the Brain City Berlin are currently closed to students, teachers and researchers due to the corona…→

© Beuth Hochschule / Karsten Flügel

Facts & EventsBuildings, lecture halls and laboratories in the Brain City Berlin are currently closed to students, teachers and researchers due to the corona…→COVID-19: Berlin universities are helping

-

Facts & Events

© ASH Berlin

Facts & EventsThe new extension building of ASH Berlin will create urgently needed space for around 1,700 students and a new refectory. The building is scheduled…→

© ASH Berlin

Facts & EventsThe new extension building of ASH Berlin will create urgently needed space for around 1,700 students and a new refectory. The building is scheduled…→Alice Salomon University celebrates topping-out ceremony

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Felix Noak

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview with Dr. phil. Thorsten Philipp, Advisor Transdisciplinary Teaching in the Office of the Vice Presidents of TU Berlin.→

© Felix Noak

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview with Dr. phil. Thorsten Philipp, Advisor Transdisciplinary Teaching in the Office of the Vice Presidents of TU Berlin.→“Everybody knows something”

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Ivar Veermae

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt EINS in Berlin-Charlottenburg, the TU Berlin supports start-ups that meet global challenges sustainably in three ways. Universities and colleges…→

© Ivar Veermae

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt EINS in Berlin-Charlottenburg, the TU Berlin supports start-ups that meet global challenges sustainably in three ways. Universities and colleges…→Economical, ecological, social

-

Facts & Events

Foto: @Harf Zimmermann, 3-D-Visualisierung@ Tonio Freitag

Facts & Events“Berlin wants to know”: “Wissensstadt Berlin 2021” is getting underway with a large open-air exhibition in front of the Rotes Rathaus.→

Foto: @Harf Zimmermann, 3-D-Visualisierung@ Tonio Freitag

Facts & Events“Berlin wants to know”: “Wissensstadt Berlin 2021” is getting underway with a large open-air exhibition in front of the Rotes Rathaus.→“Wissensstadt Berlin 2021” – Festival of Research

-

Facts & Events

Berlin Science Week 2025 © Design: Bjoern Wolf / Graphic: Martin Naumann

Facts & EventsFrom 1 to 10 November, Berlin Science Week once again invites you to explore Brain City Berlin. This year’s motto “BEYOND NOW”.→

Berlin Science Week 2025 © Design: Bjoern Wolf / Graphic: Martin Naumann

Facts & EventsFrom 1 to 10 November, Berlin Science Week once again invites you to explore Brain City Berlin. This year’s motto “BEYOND NOW”.→Opening new perspectives: Berlin Science Week 2025

-

Facts & Events

Photo: Heiner Witte/Wissenschaft im Dialog

Facts & EventsFull steam ahead! From 3 to 8 May, the ‘MS Wissenschaft’ will be anchoring at the Schiffbauerdamm in Brain City Berlin.→

Photo: Heiner Witte/Wissenschaft im Dialog

Facts & EventsFull steam ahead! From 3 to 8 May, the ‘MS Wissenschaft’ will be anchoring at the Schiffbauerdamm in Brain City Berlin.→Exhibition tip: MS Wissenschaft in Berlin

-

Insights

Photo (private)

InsightsGuest article by Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Rainer Zeichhardt, Professor for General Business Administration at the BSP – Business & Law School…→

Photo (private)

InsightsGuest article by Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Rainer Zeichhardt, Professor for General Business Administration at the BSP – Business & Law School…→New Work – new working concepts for sustainable corporate cultures

-

Facts & Events

Facts & EventsAs part of the “Creative Cities Challenge”, the “Global Innovation Collaborative” is now looking for innovative solutions that will contribute to the…→

Facts & EventsAs part of the “Creative Cities Challenge”, the “Global Innovation Collaborative” is now looking for innovative solutions that will contribute to the…→Apply until August 3: Call for Competition Entries “Creative Cities Challenge 2021”

-

Facts & Events

Credit: Berlin Partner/Wüstenhagen

Facts & EventsThe online event “Redefining the Smart City” on 23 and 24 March is inviting international researchers and Smart City experts to various workshops.The…→

Credit: Berlin Partner/Wüstenhagen

Facts & EventsThe online event “Redefining the Smart City” on 23 and 24 March is inviting international researchers and Smart City experts to various workshops.The…→International symposium on the subject of Smart Cities

-

Insights Transfer – Stories Innovations

© Berlin Partner

Insights Transfer – Stories InnovationsQuantum technology is considered to be the next big technological leap. The Brain City Berlin offers ideal conditions for this.→

© Berlin Partner

Insights Transfer – Stories InnovationsQuantum technology is considered to be the next big technological leap. The Brain City Berlin offers ideal conditions for this.→BERLIN QUANTUM: a new initiative for quantum technologies

-

Transfer – Stories

Gudrun Piechotta-Henze

Transfer – StoriesIn time for the 2020/21 winter semester, ASH, the Alice Salomon University of Applied Sciences Berlin, is launching the first bachelor's degree to…→

Gudrun Piechotta-Henze

Transfer – StoriesIn time for the 2020/21 winter semester, ASH, the Alice Salomon University of Applied Sciences Berlin, is launching the first bachelor's degree to…→"We have to completely rethink nursing!" | 27.09.2019

-

Facts & Events

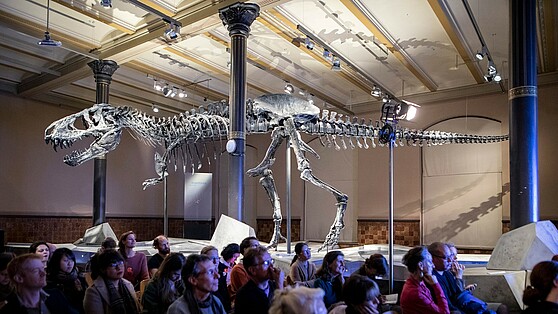

Photo: © Falling Walls Foundation

Facts & EventsWhether the Berlin Science Week, the Lange Nacht der Wissenschaften or the return of the dinosaur star Tristan Otto to Berlin: This year, the Brain…→

Photo: © Falling Walls Foundation

Facts & EventsWhether the Berlin Science Week, the Lange Nacht der Wissenschaften or the return of the dinosaur star Tristan Otto to Berlin: This year, the Brain…→Brain City Highlights 2022: Our Top 10

-

Facts & Events

© Retusche: Ralitsa Kirova/Wissenschaft im Dialog CCBY-SA4.0

Facts & EventsFrom 14 May, the floating science centre “MS Wissenschaft” will once again embark on a long voyage through Germany with an interactive exhibition on…→

© Retusche: Ralitsa Kirova/Wissenschaft im Dialog CCBY-SA4.0

Facts & EventsFrom 14 May, the floating science centre “MS Wissenschaft” will once again embark on a long voyage through Germany with an interactive exhibition on…→All aboard! MS Wissenschaft on tour

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© BettaF!sh/Valentin Pellio

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe start-up BettaF!sh develops and produces the world's first authentic seaweed-based fish alternatives in Brain City Berlin.→

© BettaF!sh/Valentin Pellio

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe start-up BettaF!sh develops and produces the world's first authentic seaweed-based fish alternatives in Brain City Berlin.→“We are breaking new ground with everything we do”

-

Facts & Events

![[Translate to English:] Peitz/Charité [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/8/csm_gabrysch-peitzsch-charite_558x314_5e9e7fccac.jpg) [Translate to English:] Peitz/Charité

Facts & EventsThe Brain City Berlin once again gets top-class new scientists: The medician and epidemiologist Prof. Dr. Dr. Sabine Gabrysch is the first female…→

[Translate to English:] Peitz/Charité

Facts & EventsThe Brain City Berlin once again gets top-class new scientists: The medician and epidemiologist Prof. Dr. Dr. Sabine Gabrysch is the first female…→First nationwide professorship for climate change and health in Berlin | 26.06.2019

-

Facts & Events

©IFAF

Facts & Events22.11.2019 | Interdisciplinarity is a central characteristic of science and research in Berlin. This was most recently proven when the Berlin…→

©IFAF

Facts & Events22.11.2019 | Interdisciplinarity is a central characteristic of science and research in Berlin. This was most recently proven when the Berlin…→IFAF Berlin marks 10th anniversary

-

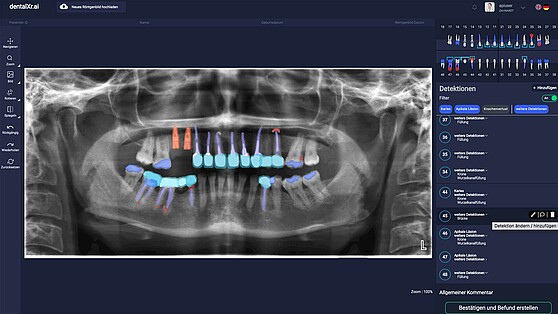

Transfer – Stories

dentalXr.ai

Transfer – StoriesdentalXrai is the first dental start-up to be spun off the Charité. It was launched via the accelerator of the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). We…→

dentalXr.ai

Transfer – StoriesdentalXrai is the first dental start-up to be spun off the Charité. It was launched via the accelerator of the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). We…→Artificial intelligence in the fight against tooth decay

-

Facts & Events

Credit: Tag der Deutschen Einheit Halle (Saale)

Facts & EventsOn 3 October, Brain City Berlin will be represented with the “Berlin Cube” at the EinheitsEXPO in Saxony-Anhalt.→

Credit: Tag der Deutschen Einheit Halle (Saale)

Facts & EventsOn 3 October, Brain City Berlin will be represented with the “Berlin Cube” at the EinheitsEXPO in Saxony-Anhalt.→#BRAINCITYBERLIN at the Day of German Unity

-

Startup Transfer – Stories

© Quantistry

Startup Transfer – StoriesThe Berlin start-up Quantistry makes chemical experiments in digital space possible with the help of Artificial Intelligence and quantum chemical…→

© Quantistry

Startup Transfer – StoriesThe Berlin start-up Quantistry makes chemical experiments in digital space possible with the help of Artificial Intelligence and quantum chemical…→The chemistry lab in the cloud

-

Facts & Events

©visitBerlin/Sarah Lindemann

Facts & EventsReal-world Laboratories are bringing scientists together with practitioners to develop solutions to the questions of tomorrow in an experimental…→

©visitBerlin/Sarah Lindemann

Facts & EventsReal-world Laboratories are bringing scientists together with practitioners to develop solutions to the questions of tomorrow in an experimental…→The "StadtManufaktur Berlin" Exhibition: experiments to create a city worth living in

-

Facts & Events

© ESMT Berlin/Fotografin: Annette Korrol

Facts & EventsAlso a great outcome for Brain City Berlin: Özlem Bedre-Defolie, Associate Professor of Economics at the ESMT Berlin international business school has…→

© ESMT Berlin/Fotografin: Annette Korrol

Facts & EventsAlso a great outcome for Brain City Berlin: Özlem Bedre-Defolie, Associate Professor of Economics at the ESMT Berlin international business school has…→On the trail of dominant platforms: ESMT Professor receives around 1.5 million euro in grant funding | 11.09.2019

-

Facts & Events

LNDM: Kulturprojekte © Christian Kielmann

Facts & EventsDo you get bored during the holidays? The Brain City Berlin offers a whole load of variety! Here are our holiday favourites.→

LNDM: Kulturprojekte © Christian Kielmann

Facts & EventsDo you get bored during the holidays? The Brain City Berlin offers a whole load of variety! Here are our holiday favourites.→10 tips for the summer

-

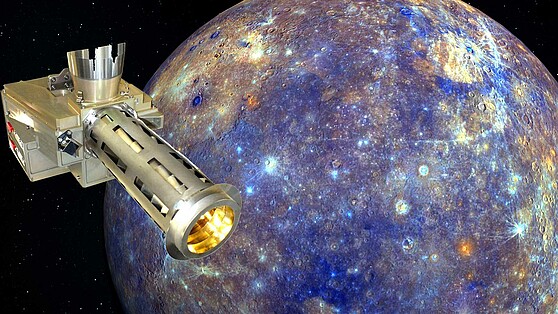

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© DLR (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWith the newly founded institute, the German Aerospace Center is pooling its expertise in the field of space instruments and space research in Brain…→

© DLR (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWith the newly founded institute, the German Aerospace Center is pooling its expertise in the field of space instruments and space research in Brain…→New DLR Institute of Space Research

-

Facts & Events

© Dirk Lamprecht / Visual Noise

Facts & EventsThe KinderUni Lichtenberg is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year with a “KUL Science Day” and an exciting series of lectures.→

© Dirk Lamprecht / Visual Noise

Facts & EventsThe KinderUni Lichtenberg is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year with a “KUL Science Day” and an exciting series of lectures.→From “Sweet, tasty – and dangerous” to “Riding a bike hands-free” - KUL lectures for children

-

Facts & Events

© Agentur Medienlabor/Benjamin Maltry

Facts & EventsThe jury presented five awards and one special award for particularly innovative products, concepts and solutions from the capital region.→

© Agentur Medienlabor/Benjamin Maltry

Facts & EventsThe jury presented five awards and one special award for particularly innovative products, concepts and solutions from the capital region.→Berlin Brandenburg Innovation Award: the winners 2022

-

Facts & Events

Facts & EventsThe Berlin universities of applied sciences – four State and two denominational – are celebrating their anniversaries. On the occasion of the joint…→

Facts & EventsThe Berlin universities of applied sciences – four State and two denominational – are celebrating their anniversaries. On the occasion of the joint…→50 Years – 50 Stories

-

Facts & Events

© DGZfP

Facts & EventsMany exciting and high-calibre events are once again on the Brain City Berlin event calendar this year. We present our favourites to you.→

© DGZfP

Facts & EventsMany exciting and high-calibre events are once again on the Brain City Berlin event calendar this year. We present our favourites to you.→Brain City Berlin 2023: the Top 10 Events

-

Facts & Events

MPG © Hallbauer und Fioretti

Facts & EventsThe Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has given top Berlin researcher Professor Dr Emmanuelle Charpentier and American Professor Dr Jennifer A. Doudna…→

MPG © Hallbauer und Fioretti

Facts & EventsThe Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has given top Berlin researcher Professor Dr Emmanuelle Charpentier and American Professor Dr Jennifer A. Doudna…→2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry goes to Emmanuelle Charpentier: Congratulations!

-

Transfer – Stories

Photo: Mall Anders/Matthew Crabbe

Transfer – Stories“Mall Anders” is an open learning laboratory which was launched by the FU Berlin, HU Berlin, TU Berlin and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in a…→

Photo: Mall Anders/Matthew Crabbe

Transfer – Stories“Mall Anders” is an open learning laboratory which was launched by the FU Berlin, HU Berlin, TU Berlin and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in a…→Science in a Shopping Centre

-

Insights Facts & Events

© Bundespreis Ecodesign. Urheber/in: IDZ Berlin

Insights Facts & Events“Mach Moor - Design with Paludiculture”: An Exhibition on Peatland Protection in Berlin→

© Bundespreis Ecodesign. Urheber/in: IDZ Berlin

Insights Facts & Events“Mach Moor - Design with Paludiculture”: An Exhibition on Peatland Protection in Berlin→“Mach Moor - Design with Paludiculture”: An Exhibition on Peatland Protection in Berlin

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_Open-Access_Berlin-Partner_Wu__stenhagen_558x314_dd0c6e714d.jpg) [Translate to English:]

Transfer – StoriesScience and cultural heritage, freely accessible to everyone at any time on the Internet: The Open Access movement is promoting a paradigm shift in…→

[Translate to English:]

Transfer – StoriesScience and cultural heritage, freely accessible to everyone at any time on the Internet: The Open Access movement is promoting a paradigm shift in…→Knowledge for All - Open Access in Berlin | 28.03.2019

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Berlin Partner/Wüstenhagen

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe focus is on the science location, the science and technology transfer that is characteristic of Berlin – and of course the Brain City Ambassadors.…→

© Berlin Partner/Wüstenhagen

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe focus is on the science location, the science and technology transfer that is characteristic of Berlin – and of course the Brain City Ambassadors.…→Brain City Berlin launches new campaign motifs

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Berlin University Alliance / Stefan Klenke

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the innovate! lab, the Berlin University Alliance (BUA) aims to bring cutting-edge research into practice quickly and purposefully. Dr.…→

© Berlin University Alliance / Stefan Klenke

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the innovate! lab, the Berlin University Alliance (BUA) aims to bring cutting-edge research into practice quickly and purposefully. Dr.…→“Research transfer through agility”

-

Facts & Events

Matthias Heyde, HU Berlin

Facts & EventsThe new Unter den Linden underground station is currently teeming with science. An exhibition organised by the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin shows…→

Matthias Heyde, HU Berlin

Facts & EventsThe new Unter den Linden underground station is currently teeming with science. An exhibition organised by the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin shows…→Exhibition tip: Science Underground

-

Facts & Events

© HTW Berlin/ Alexander Rentsch

Facts & EventsAt 51 percent, Brain City Berlin has the highest rate of first-time university graduates in Germany.→

© HTW Berlin/ Alexander Rentsch

Facts & EventsAt 51 percent, Brain City Berlin has the highest rate of first-time university graduates in Germany.→First university degrees: Berlin in top position nationwide in 2023

-

Transfer – Stories

HIIG

Transfer – StoriesBrain City-Interview with Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schulz, Research Director at the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society (HIIG).→

HIIG

Transfer – StoriesBrain City-Interview with Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schulz, Research Director at the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society (HIIG).→“A sustainable goal of our work is to make clear what the technology can actually do”

-

Transfer – Stories

©Credit Silke Oßwald/FMP

Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview: Professor Dr. Volker Haucke, Director at the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP) and Professor of…→

©Credit Silke Oßwald/FMP

Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview: Professor Dr. Volker Haucke, Director at the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP) and Professor of…→In the balancing act between detail and overall concept

-

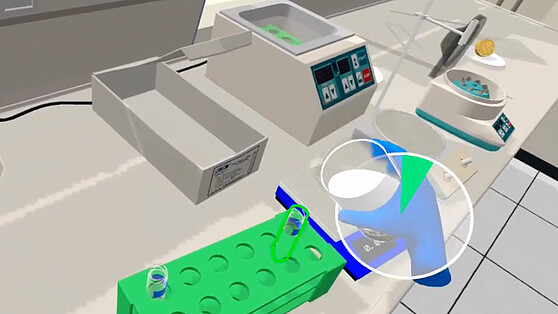

Insights Transfer – Stories

© BHT-MINT-VR-Labs

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt the MINT VR labs at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik, an interdisciplinary team works on didactic concepts for virtual laboratories and…→

© BHT-MINT-VR-Labs

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt the MINT VR labs at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik, an interdisciplinary team works on didactic concepts for virtual laboratories and…→Learning through play in the virtual bio-lab

-

Facts & Events

© SPB/Natalie Toczek

Facts & Events100 years of the Planetarium: On 21 October, the Zeiss-Großplanetarium celebrates the star show anniversary with a colourful program of astronomy,…→

© SPB/Natalie Toczek

Facts & Events100 years of the Planetarium: On 21 October, the Zeiss-Großplanetarium celebrates the star show anniversary with a colourful program of astronomy,…→Travel to space for free

-

Facts & Events

© mfn / Carola Radke

Facts & EventsOn 6 October, the mit:forschen! team invites you to the first Campus Citizen Science event at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin.→

© mfn / Carola Radke

Facts & EventsOn 6 October, the mit:forschen! team invites you to the first Campus Citizen Science event at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin.→Campus Citizen Science: Artificial Intelligence

-

Facts & Events

©ADN Broadcast

Facts & Events31.10.2019 | For the second time, a Falling Walls Lab was held in Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, on 21 September 2019. The event was organized by…→

©ADN Broadcast

Facts & Events31.10.2019 | For the second time, a Falling Walls Lab was held in Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, on 21 September 2019. The event was organized by…→Brain City Ambassador organizes 2nd Falling Walls Lab in Tunis

-

Facts & Events

© wörner traxler richter planungsgesellschaft mbH

Facts & EventsThe Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the German Heart Center Berlin (DHZB) will pool their competencies from January 2023. By 2028, one of the…→

© wörner traxler richter planungsgesellschaft mbH

Facts & EventsThe Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the German Heart Center Berlin (DHZB) will pool their competencies from January 2023. By 2028, one of the…→New Heart Center for Berlin

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt the business and science location Berlin Schöneweide, tradition meets the ideas and solutions of tomorrow. The scientific nucleus of the area: the…→

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt the business and science location Berlin Schöneweide, tradition meets the ideas and solutions of tomorrow. The scientific nucleus of the area: the…→A place of innovation and transformation

-

©vdo

Every year, just before Christmas evening, we ask ourselves full of hope the same question: Will there be White Christmas? According to the Berliner…→

©vdo

Every year, just before Christmas evening, we ask ourselves full of hope the same question: Will there be White Christmas? According to the Berliner…→Whether green or white: We wish you a Merry Christmas!

-

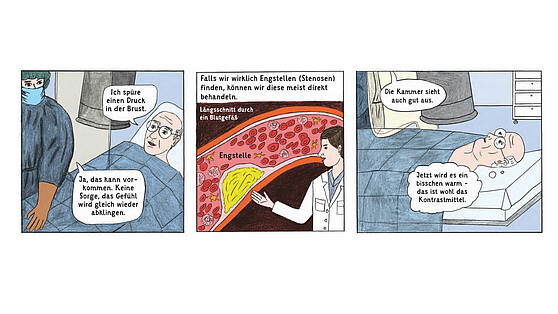

Facts & Events Innovations

© Brand, Gao, Hamann, Martineck, Stangl/Charité

Facts & Events InnovationsThe Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin wants to inform patients with a comic before a heart catheter examination. As part of a study, the…→

© Brand, Gao, Hamann, Martineck, Stangl/Charité

Facts & Events InnovationsThe Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin wants to inform patients with a comic before a heart catheter examination. As part of a study, the…→A picture is worth a thousand words

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

TU Berlin © Felix Noak

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesInterdisciplinary research teams have until 29 April to submit their proposals for the Next Grand Challenge initiative of the Berlin University…→

TU Berlin © Felix Noak

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesInterdisciplinary research teams have until 29 April to submit their proposals for the Next Grand Challenge initiative of the Berlin University…→Next Grand Challenge: apply now!

-

Facts & Events

© Adobe Stock/stockartstudio

Facts & EventsThe Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin has almost doubled the proportion of women in professorships in around 15 years. The gender ratio among academic…→

© Adobe Stock/stockartstudio

Facts & EventsThe Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin has almost doubled the proportion of women in professorships in around 15 years. The gender ratio among academic…→HU Berlin: more women in science

-

Transfer – Stories

©Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin/Matthias Heyde

Transfer – StoriesThe courses offered by the HUWISU Summer University are varied and exciting, the target group is international: students from abroad who come to…→

©Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin/Matthias Heyde

Transfer – StoriesThe courses offered by the HUWISU Summer University are varied and exciting, the target group is international: students from abroad who come to…→When Berlin becomes one large seminar room ... | 15.08.2019

-

Facts & Events

©Samuel Henne

Facts & EventsThe exhibition MACHT NATUR at STATE Studio in Berlin focuses on the discomfort that many of us experience when faced with human intervention in…→

©Samuel Henne

Facts & EventsThe exhibition MACHT NATUR at STATE Studio in Berlin focuses on the discomfort that many of us experience when faced with human intervention in…→MACHT NATUR: an exhibition that asks questions

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Maschinenraum

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesThe University of Applied Sciences wants to tap additional transfer potential by means of cooperation with the nationwide network of SMEs.→

© Maschinenraum

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesThe University of Applied Sciences wants to tap additional transfer potential by means of cooperation with the nationwide network of SMEs.→HTW Berlin cooperates with Maschinenraum

-

Insights

Dr. Anja Sommerfeld (private)/ Dr. Gregor Hofmann (David Ausserhofer)

InsightsBrain City interview with D. Anja Sommerfeld und Dr Gregor Hofmann of Berlin Research 50. The initiative of Berlin’s non-university research…→

Dr. Anja Sommerfeld (private)/ Dr. Gregor Hofmann (David Ausserhofer)

InsightsBrain City interview with D. Anja Sommerfeld und Dr Gregor Hofmann of Berlin Research 50. The initiative of Berlin’s non-university research…→Getting the Best out of Berlin as a Science Hub

-

Transfer – Stories

(From left to right) Steffen Terberl/FU Berlin; Prof. Dr. Hannes Rothe/ICN Business School, photo: Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Transfer – StoriesIn the BioTech sector, the Berlin region is not making full use of its innovation potential. This is the conclusion of the “Deep Tech Futures Report…→

(From left to right) Steffen Terberl/FU Berlin; Prof. Dr. Hannes Rothe/ICN Business School, photo: Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Transfer – StoriesIn the BioTech sector, the Berlin region is not making full use of its innovation potential. This is the conclusion of the “Deep Tech Futures Report…→“BioTech does not get up and running on its own”

-

Facts & Events

© Berlin Partner / Elvina Kulinicenko

Facts & EventsIn October/November, construction began on three prominent research buildings in Berlin, and another was officially opened. Here’s an overview.→

© Berlin Partner / Elvina Kulinicenko

Facts & EventsIn October/November, construction began on three prominent research buildings in Berlin, and another was officially opened. Here’s an overview.→Showcases, Hubs and Innovation Platforms: What’s new in Brain City Berlin?

-

Facts & Events

© Shutterstock. AI Generator

Facts & EventsDo stable relationships matter more to women or to men? A study, in which the Institute of Psychology at HU Berlin was involved in a leading role,…→

© Shutterstock. AI Generator

Facts & EventsDo stable relationships matter more to women or to men? A study, in which the Institute of Psychology at HU Berlin was involved in a leading role,…→Romantic Gender Gap

-

Facts & Events

© Senatsverwaltung für Wissenschaft, Gesundheit, Pflege und Gleichstellung

Facts & EventsProposals can be submitted until 14 November 2022. The award, presented by the Senate Department for Higher Education and Research, Health, Long-Term…→

© Senatsverwaltung für Wissenschaft, Gesundheit, Pflege und Gleichstellung

Facts & EventsProposals can be submitted until 14 November 2022. The award, presented by the Senate Department for Higher Education and Research, Health, Long-Term…→Berliner Frauenpreis 2023

-

Transfer – Stories

Swen Hutter (Foto: David Ausserhofer), Gesine Höltmann (Foto: Martina Sander)

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Gesine Höltmann, research assistant and Swen Hutter, Deputy Director at the Centre for Civil Society Research.→

Swen Hutter (Foto: David Ausserhofer), Gesine Höltmann (Foto: Martina Sander)

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Gesine Höltmann, research assistant and Swen Hutter, Deputy Director at the Centre for Civil Society Research.→Polarisation and Cohesion in the Corona Crisis: a Look at Civil Society

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© vdo

Insights Transfer – StoriesProf. Dr. Claus Bull and Dipl.-Ing. Dirk Jäger at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik are investigating what street trees need to survive and how they…→

© vdo

Insights Transfer – StoriesProf. Dr. Claus Bull and Dipl.-Ing. Dirk Jäger at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik are investigating what street trees need to survive and how they…→“The trees in the city have a lot to put up with”

-

Facts & Events

Fu Berlin / Peter Hirnsel

Facts & EventsBerlin is a cosmopolitan metropolis. People from more than 190 countries live and work in the city. More and more young, talented people who would…→

Fu Berlin / Peter Hirnsel

Facts & EventsBerlin is a cosmopolitan metropolis. People from more than 190 countries live and work in the city. More and more young, talented people who would…→Berlin universities are extraordinarily international | 10.10.2019

-

Facts & Events

© HWR Berlin/Lukas Schramm

Facts & EventsStudy – yes. But at which university? And above all: which subject? This year, Berlin’s universities and colleges are once again inviting students to…→

© HWR Berlin/Lukas Schramm

Facts & EventsStudy – yes. But at which university? And above all: which subject? This year, Berlin’s universities and colleges are once again inviting students to…→Student Information Days 2024

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe KI-Werkstatt at the HTW Berlin brings together the university’s expertise in an interdisciplinary manner to research the practical use of AI.→

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe KI-Werkstatt at the HTW Berlin brings together the university’s expertise in an interdisciplinary manner to research the practical use of AI.→Strengthening generative AI in research and teaching

-

Transfer – Stories

Foto: ESCP Business School Berlin

Transfer – StoriesWhat to do when distance is suddenly the order of the day? A guest contribution by Dr. René Mauer, Professor of Entrepreneurship und Innovation at…→

Foto: ESCP Business School Berlin

Transfer – StoriesWhat to do when distance is suddenly the order of the day? A guest contribution by Dr. René Mauer, Professor of Entrepreneurship und Innovation at…→Using Whiteboards to Combat Digital Fatigue

-

Facts & Events

©TU Berlin Pressestelle / Dahl

Facts & EventsThe coronavirus pandemic carries many risks, not only for individuals, but also for society. But how are the risks being perceived? And how are people…→

©TU Berlin Pressestelle / Dahl

Facts & EventsThe coronavirus pandemic carries many risks, not only for individuals, but also for society. But how are the risks being perceived? And how are people…→Risk perception in the coronavirus crisis: a survey from TU Berlin

-

Facts & Events

©Paul Hahn Photography

Facts & EventsBerlin's Senator for Economics, Ramona Pop, and Brandenburg's Minister of Economic Affairs, Jörgs Steinbach, have once again announced the search for…→

©Paul Hahn Photography

Facts & EventsBerlin's Senator for Economics, Ramona Pop, and Brandenburg's Minister of Economic Affairs, Jörgs Steinbach, have once again announced the search for…→2020 Innovation Award: Apply by 22th June!

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© TU Berlin / allefarben-foto

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesDrone logistics, recycling of building material and wastewater reuse: these ideas are to be tested in so-called “Reallaboren” (Real-World…→

© TU Berlin / allefarben-foto

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesDrone logistics, recycling of building material and wastewater reuse: these ideas are to be tested in so-called “Reallaboren” (Real-World…→Three Real-World Laboratories are being Launched in Berlin

-

Facts & Events

©Mario Gogh/Unsplash

Facts & EventsStart-ups arising from research being done at Berlin's universities are of major importance for the region's economy. As the “Gruendungsumfrage 2020”…→

©Mario Gogh/Unsplash

Facts & EventsStart-ups arising from research being done at Berlin's universities are of major importance for the region's economy. As the “Gruendungsumfrage 2020”…→Academic start-ups strengthen Berlin's economy

-

Insights Facts & Events

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Insights Facts & EventsIt's all about future food production: in the CUBES Circle project, scientists are researching how established agricultural production systems can be…→

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Insights Facts & EventsIt's all about future food production: in the CUBES Circle project, scientists are researching how established agricultural production systems can be…→Tomatoes and fish in a zero-waste cycle

-

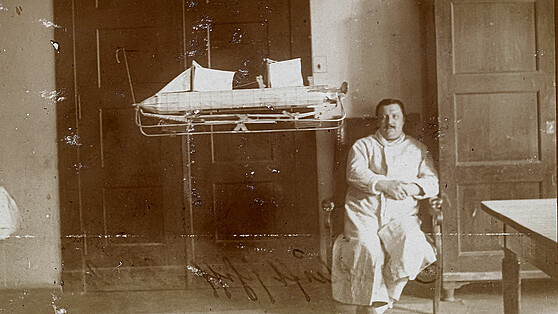

Facts & Events

© Institute for the History of Medicine and Medical Ethics, Charité (IGM-K-HPAC 3086-1908)

Facts & EventsIn the exhibition “Inventing-Mania!”, the Berlin Museum of Medical History tells the story of “Engineer von Tarden” and his sailing airship.→

© Institute for the History of Medicine and Medical Ethics, Charité (IGM-K-HPAC 3086-1908)