-

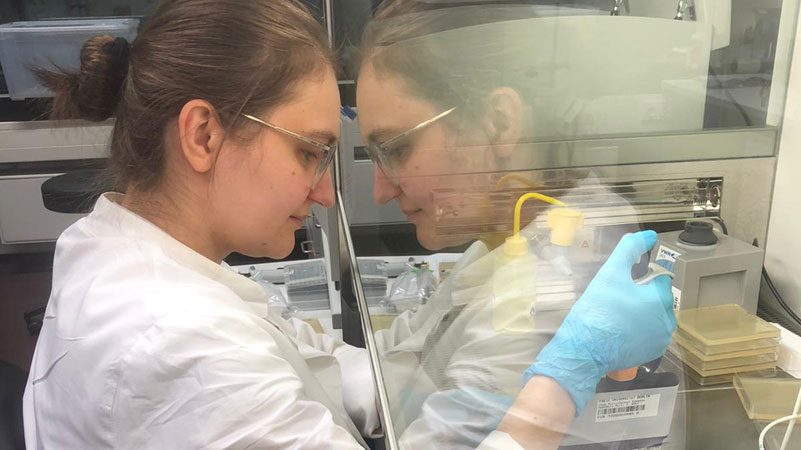

Foto: Olga Makarova privat

11.02.2021Guest contribution: COVID-19 and microbiology literacy

Brain City Berlin Ambassador Olga Makarova, PhD,reflects on being a microbiologist during the pandemic, and the urgent need for microbiology literacy in society.

A little more than a year ago, in November 2019, I arrived in Hong Kong. I was full of excitement: first time in South East Asia and en route to UNLEASH – the largest innovation lab for UN Sustainable Development Goals, SDGs. As a microbiologist working on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), an emergent threat that undermines modern medicine, my ambition, of course, was to bring awareness to the importance of microbiology literacy and infectious diseases in the society.

On my last day in Hong Kong, out of academic curiosity, I decided to visit a traditional wet market. In such places, various animals are kept alive to preserve the freshness of the produce. This also increases the risk of zoonotic (animal-to-human transmission) disease outbreaks, and that was precisely what happened with SARS-1, a deadly coronavirus that wreaked havoc around South East Asia almost twenty years ago. Although highly publicised in 2002-2004, coronaviruses would hardly ring the bell among general population in 2019. Little did I know that history was repeating itself and a related strain of coronavirus – at the time unknown but later named as SARS-CoV-2 – would be soon be making an appearance at another wet market, just a few hundred kilometres north.

Pandemic at the doorstep

Fast-forward to March 2020: coronaviruses are a household name and the demand for microbiology knowledge is as high as ever. The first request – an inquiry to consult about alternative disinfectants (I research biocide resistance) arrived in my email in February. In the weeks that followed, friends and family would frequently get in touch asking questions about the new disease and how not to get infected. UNLEASH promptly organises a COVID-19 hackathon, where I serve as an expert.

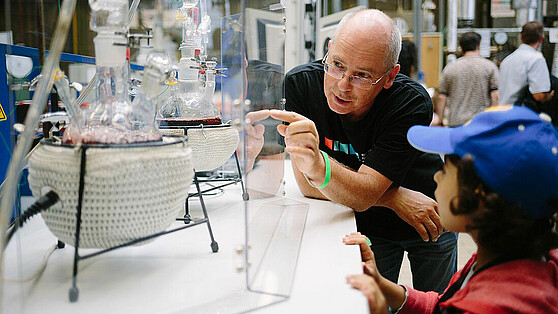

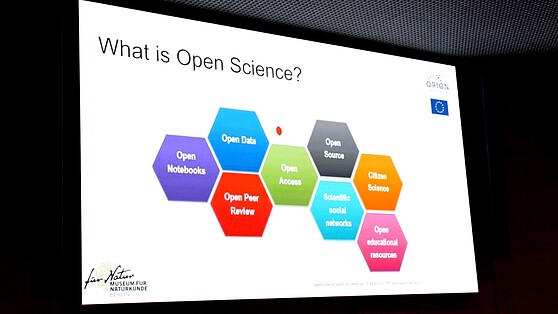

In a short time, the coronavirus turned everyone’s lives upside down, including those of scientists. But researchers around the world quickly found ways of working together to fight the unfolding health emergency: from curating open source projects, volunteering time and expertise to signing up on reserve lists of molecular biologists to help local diagnostics efforts. Even major publishers lifted their pay-walls. Despite the hardship, it suddenly felt good to be in research: the scientific community embraced open exchange and collaboration, forgetting about extreme competition and paper-chasing that normally define it. Science was declared the only way out of the pandemic and society became deeply aware of its importance.

I too decide to contribute my skills and knowledge

Initially unable to go to the lab, I started a collaboration with three other scientists from Berlin – physicist Sebastian Stolzenberg from the Freie Universität Berlin, immunologist Weijie Du, from the German Rheumatology Research Center Berlin and molecular biologist Junxue Dong from Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology. Together, by combining our diverse expertise, we wanted to develop an AI-powered platform for a T-cell based antiviral immunotherapy of COVID-19. Later, we won the special Corona prize at the Berlin University Alliance “Research-to-Market Challenge” business idea competition. The prize money, without hesitation, were donated to COVID-19 causes.

Shortly before Easter, I was asked to urgently return to the lab and set up molecular diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2. This is necessary to help investigations on how the virus spreads through the air and its stability in the environment, as well as for testing the efficiency of masks. Spending the holidays organising supplies and preparing protocols for handling the virus in the lab was an intense experience. As many labs in spring 2020, we struggled with obtaining personal protective equipment (PPE), reagents for molecular diagnostics and an extreme workload – cognitive as much as physical. In microbiology labs, a thorough risk assessment and detailed contingency plans for a new pathogen must be made in advance. Simply put, you are not allowed to enter the lab until you know exactly what you are doing (especially in case something goes wrong!). But in the early spring, the information about SARS-CoV-2 was sparsely available, so I had to turn to what was known about SARS-1 (which was terrifying!). Meanwhile, to protect the health of researchers, the lab was operating on the minimal presence basis. This meant working long hours alone, and for some scientists (myself inclusive), this also meant picking up the pipette again after years away from the bench.

The first samples arrived in an ice box early in the evening

The collection tubes were shaped not unlike champagne glasses and contained pink liquid, making it all look like glasses of rose wine. Except those were samples of the air from intensive care units at the Berlin’s Charité hospital (drinking which was certainly not advisable!). The goal was to investigate the presence of the virus in the air so that hospital personnel could better understand the risks. SARS-CoV-2 is a RNA virus, and RNA is an extremely fragile molecule. I therefore decided to process the samples right away.

The first step was to filter the samples, which were stored in an air collection medium, by pressing it through a 0.22 µm membrane. This is a relatively straightforward procedure, albeit prone to generation of splashes and therefore performed inside a biosafety cabinet. Carefully, I started drawing the viral sample with a long needle when I noticed untypical resistance. As it turned out, the medium was additionally spiked with a substance that made it unusually viscous, and thus extremely hard to filter. Overheating from all the physical effort (and PPE), with foggy glasses constantly attempting to slide down the respirator and hands inside the biosafety hood operating 10 cm long syringes, those were some of the more memorable moments indeed. Needless to say, it took a lot more time and effort to finish. That day I left the lab well past midnight, but safe in the knowledge that the air in ICUs was safe. This information was immediately passed on to our colleagues at Charité. And while all this sounds challenging, there was also a shared sense of excitement: our research was having an impact in real life!

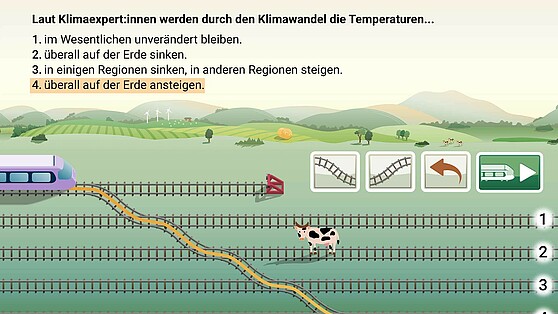

A little of microbiology literacy goes a long way

Although talks of a major infectious disease outbreak happening in the not-so-distant future (disease X) have been circulating within the infection medicine field for decades, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the COVID-19 pandemic caught many countries off-guard. Arguably, there are many reasons for that, but one thing is clear: a better understanding of microbiology and related disciplines by non-specialists could have a massive impact on how things played out. From the strategies that governments adopt (quarantine vs controlled spread) to acceptance of new measures (such as distancing, masks, vaccine uptake) by the general population – a basic understanding of microbiology is critical. It was also clear that countries with sustained funding of research and public health infrastructure were able to mount a more efficient response.

Winston Churchill was quoted once saying: "Never let a good crisis go to waste". I would like to argue that despite the enormous amount of suffering (in part, due to the lack of microbiology literacy) the COVID-19 crisis brought on, it also presented us as a society with a unique opportunity to re-imagine our relationship with (microbial) sciences. More than ever before, I am confident that science will lead us out of the current crisis. I am also convinced it will not be the last major public health emergency. So let’s continue keeping the public awareness and engagement levels high and advocate for better support of science. Because, paraphrasing a popular expression, if you think microbiology knowledge is expensive, try ignorance.

Olga Makarova is an infection biologist at the Centre for Infection Medicine, Department of Veterinary Medicine at Freie Universität Berlin, an UNLEASH SDG3 global talent, a 2019/2020 WikimediaDE Open Science Fellow, and a Brain City Berlin ambassador. Her professional interests revolve around various aspects of antimicrobial resistance, coronaviruses, open science, entrepreneurship and science policy.

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/d/csm_bwasihun-vdo_558x314_c0d384ce60.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Berlin University Alliance/Matthias Heyde [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/a/csm_Berlin_University_Alliance_Matthias_Heyde-558x314_4bc591ca3c.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] David Ausserhofer/IGB [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/f/csm_Hupfer__Michael_____R__David_Ausserhofer_588x314_6fef164e57.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_helena-lopes-1338810-unsplash_558x314_857802ad2f.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] HZB/M. Setzpfandt [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/a/csm_LNDW_HZB_558x314_e1e3500ed5.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Tim Landgraf [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/7/csm_Car2CarEnergySharing_Tim_Landgraf_558x314_485bf716e9.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_Open-Access_Berlin-Partner_Wu__stenhagen_558x314_dd0c6e714d.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Thomas Rosenthal - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/d/csm_Museum_fu___er_Naturkunde_Berlin_Thomas_Rosenthal_f11b8ba056.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/c/csm_TU_Berlin_Cem_Avsar_558x314_4b07bcb055.jpg)