-

© Felix Noak

21.09.2022“Everybody knows something”

Das Wort ist für viele neu und nicht immer verständlich: Transdisziplinarität bezeichnet ein Denken und Arbeiten über die Grenzen von wissenschaftlichen Disziplinen hinaus. Sie reicht dabei deutlich weiter als Interdisziplinarität. Transdisziplinäre Forschung ist vielmehr eng mit der Gesellschaft verzahnt, denn sie bezieht vielfältige Wissensressourcen ein. Mit teilweise erstaunlichen Ergebnissen, wie zahlreiche Citizen-Science-Projekte in der Brain City Berlin belegen. Dr. phil. Thorsten Philipp ist Experte auf dem Gebiet. Als Referent für Transdisziplinäre Lehre im Präsidium der Technischen Universität Berlin beschäftigt er sich nicht nur theoretisch mit dem Thema. Er sucht auch nach Ansätzen, das Denken von Studierenden über die eigene Disziplin hinaus zu erweitern – in die Gesellschaft hinein. Mehr darüber erzählt er im Brain City-Interview.

Dr Philipp, interdisciplinarity is currently a buzz word in science, business and many other areas of our lives. However, you deal with “transdisciplinarity”. How do you define it?

Transdisciplinarity is the attempt to develop knowledge resources beyond disciplines. It is about resources in our society that are not developed, categorised and summarised in scientific disciplines and are therefore not socially recognised.

That sounds pretty abstract. Can you give us a few examples?

Experiential knowledge and professional knowledge are part of it. Or, for example, the so-called autochthonous knowledge. This is the knowledge of indigenous communities, such as the Aborigines in Australia. For example, they have an incredible knowledge of natural active ingredients, which is of great interest for the pharmaceutical industry.

Our academic system closes itself off to valuable sources of knowledge. Why is that?

Universities are hierarchical systems. And in the end, it is a question of power which knowledge is recognised and taught and which is not. It is also a question of shaping society: Who dominates the discourse? And who has the power to promise solutions to problems? Although transdisciplinarity has been a recurring keyword in academia since the 1970s, it has established itself only hesitantly and sporadically at universities. Transdisciplinarity is now permanently institutionalised at the TU Berlin. With a staff unit “Science and Society” for transdisciplinary research at the Presidium. I myself also have a position in the Executive Committee that deals with transdisciplinary didactics, i.e. transdisciplinary teaching. This is unique in Germany so far – and already something special.

What do you deal with in your work?

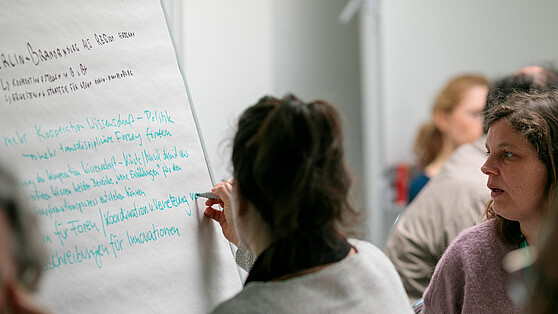

My main concern is how learning events change through transdisciplinary methods. Students are often not an issue in such projects. I believe that is because transdisciplinary research has to meet certain requirements in order to link teaching to the projects. A fundamental difficulty in transdisciplinary projects is to work with different stakeholders in society who are not scientists. That complicates the process enormously. This plurality of roles of responsibility must first be coordinated. I need to be able to find them, “evaluate” them and classify their contribution. This is usually not provided for in teaching.

Are there already examples of transdisciplinary teaching at the TU Berlin?

A whole series of didactic attempts to use transdisciplinary methods have existed at the TU Berlin for decades. The focus here is on cooperation between science and society. For example, we offer events under the keyword “Service Learning”. These are in the service of a social cause. For example, the problem of a civic engagement organisation such as BUND or a refugee service is dealt with. We bring scientific methods into problem solving, the sponsor brings practical experience. This is where learning comes into play. Ideally, at least one problem will be worked on in exchange. That is the service.

How do these courses differ from practical seminars?

The practical seminar is not necessarily under the banner of civic engagement. But there, too, a transdisciplinary perspective emerges, basically even in every internship. However, hardly anyone thinks about the extent to which transdisciplinary competence can be realised in an internship. Internships are also strongly in line with a capitalist logic of exploitation. What if we succeeded in teaching students to view internships more as a learning experience and also to record learning events in a systematic way? Unfortunately, this is still not an issue for most of those involved.

Students need to be prepared for that.

That is basically my mission. For example, to enter into dialogue with companies in order to strengthen the didactic dimensions of internships.

And how is the transdisciplinary cooperation with the various chairs at TU Berlin going?

Put simply, well. In principle, and at the TU Berlin anyway, there is a high affinity at technical universities for cooperation with “the world outside”, with industry, politics, society. It would therefore be worthwhile to think about the specific role of technical universities in the transdisciplinary discourse, which bring a high level of application relevance. In the humanities disciplines, things look quite different again. In this respect, it is also understandable that the interest in transdisciplinarity in science and research is not present in the same way everywhere. It is strong in areas such as architecture, urban development or environmental engineering. The topic is also attracting increasing interest in sociology. The universities of applied sciences also have a lot of potential with their dual study programs.

Mall Anders – open learning lab in a mall. (photo above, right: © Leo Fenster)

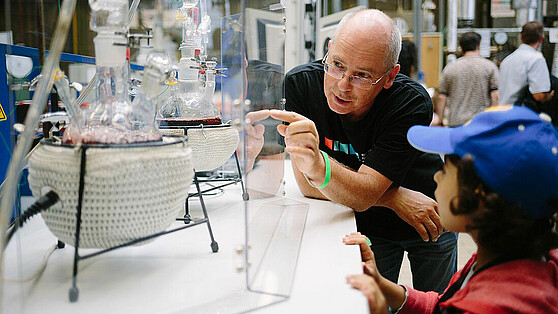

This spring and summer, together with students from Berlin’s universities of excellence, you set up "Mall Anders” as an open, transdisciplinary learning lab in a shopping mall in Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. What learning experiences have the students and also the lecturers been able to take away from the project?

For scientists, this transdisciplinary experimental space in the middle of the mall was a place of uncertainty. They often reached their communicative limits in the encounter with a new audience. This clearly highlighted the need for further training for university members in this regard. For many in our team, the students and also some academics, it was fundamentally difficult to cross the boundary between university and society – even in a shopping mall. We had to be physically and mentally present at all times in order to appeal to passers-by and attract new audiences. In the end, Mall Anders allowed us, above all, to learn about ourselves.

Is Brain City Berlin a good ground for transdisciplinary research?

Berlin is an ideal location for transdisciplinarity. The local maker culture, the abundance of FabLabs, repair cafés, the many community gardens in the city – these are all places of knowledge production and accumulation. Researchers can use this without exploiting projects. And we can get involved. Berlin is a fantastic place for that.

The Berlin University Alliance is also based on transdisciplinary approaches. How can you use this?

The BUA is an important sponsor for us. Mall Anders could not have been achieved without the Berlin Excellence Network. The beauty of BUA is that it has succeeded in transferring transdisciplinarity from its Cinderella existence to the discussion and research of excellence. Transdisciplinarity is defined in the BUA application as one of the five central goals – under the keyword “Fostering Knowledge Exchange”. And that’s what it is all about: To share knowledge resources.

The world today faces very complex challenges, the “Grand Challenges”, which BUA also takes up in its research. Such topics can no longer be researched individually, but only in an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary manner.

Absolutely. Actually, transdisciplinarity arose out of the criticism of the discipline and its design. And behind this, as with interdisciplinarity, is the experience and insight that individual disciplines are no longer suitable for solving current problems on their own. We simply can no longer afford to exclude the many valuable knowledge resources we have in our society. All people are carriers of knowledge resources. Everybody knows something.

But is this knowledge always valuable?

You have to take a closer look: What kind of problem do I have? What do I want to work on? And who can help me? In other words: Not everyone can provide valuable input to solve my problem, but many can.

Science opens up to society through transdisciplinarity. But is society also open to science? As the corona pandemic has made clear, scepticism about science is widespread in society.

We are facing a process of change on both sides. On the one hand, proponents of transdisciplinarity claim that it can help to moderate crises of legitimacy in science. Where science opens up, it may manage to reduce such crises of legitimacy. On the other hand, there are stakeholders in companies and civil society who are closed to science. As the saying goes: “They are all just ranting theorists”.

What advice would you like to give to students about your work?

Above all, an attitude with which they understand and define themselves as academics, but at the same time know about the limitations of their disciplines. An attitude about which they are permanently in dialogue and cooperation with society. They should constantly reflect and keep in mind their responsibility towards society. In my understanding, this is also the goal of transdisciplinary teaching. (vdo)

Additional information

- Mall Anders (German only)

- „Handbuch Transdisziplinäre Didaktik“, Tobias Schmohl / Thorsten Philipp (Hg.), Transkript Verlag (2021, German only), download e-book als open access publication

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/d/csm_bwasihun-vdo_558x314_c0d384ce60.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Berlin University Alliance/Matthias Heyde [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/a/csm_Berlin_University_Alliance_Matthias_Heyde-558x314_4bc591ca3c.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] David Ausserhofer/IGB [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/f/csm_Hupfer__Michael_____R__David_Ausserhofer_588x314_6fef164e57.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_helena-lopes-1338810-unsplash_558x314_857802ad2f.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] HZB/M. Setzpfandt [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/a/csm_LNDW_HZB_558x314_e1e3500ed5.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Tim Landgraf [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/7/csm_Car2CarEnergySharing_Tim_Landgraf_558x314_485bf716e9.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_Open-Access_Berlin-Partner_Wu__stenhagen_558x314_dd0c6e714d.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Thomas Rosenthal - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/d/csm_Museum_fu___er_Naturkunde_Berlin_Thomas_Rosenthal_f11b8ba056.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/c/csm_TU_Berlin_Cem_Avsar_558x314_4b07bcb055.jpg)