-

© vdo

10.08.2023“The trees in the city have a lot to put up with”

Drought and other stress factors such as de-icing salts are causing problems for the trees in Berlin. More than half of the approximately 430,000 street trees in Berlin have already been damaged. This applies above all to Berlin urban tree classics such as lime and maple. Prof. Dr. Claus Bull and Dipl.-Ing. Dirk Jäger and students from the Horticultural Phytotechnology course at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik are investigating what street trees need to survive and how they can be effectively revitalised.

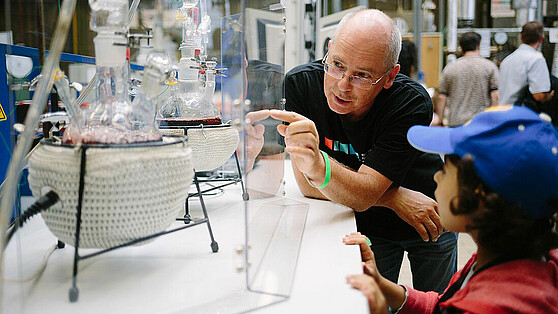

The edge of the lime leaf that Prof. Dr. Claus Bull is holding in his hand is brown and dry. Towards the inside it is yellowish discoloured, in the middle area still green. “The yellow area is what is known as chlorosis. Photosynthesis no longer takes place there due to disease. The cells die. Necrotic, i.e. dead tissue, develops. We see that on the edges.” Claus Bull is Professor of Horticultural Plant Production and Marketing at the Horticultural Phytotechnology program of the Berliner Hochschule für Technik (BHT). The scientist also heads the laboratory greenhouse at the university. Here, students learn and do research, for example, under which conditions crops such as tomatoes thrive sustainably, how nutrient cycles can be set up in a resource-saving manner, or they observe and investigate how LED lighting affects the growth and nutrient content of vegetables.

The vitalisation of urban trees is another topic that Claus Bull is investigating with his colleague Dirk Jäger as part of the courses: Behind the greenhouse on the grounds of the BHT in Berlin-Wedding, young winter lime trees are lined up in test blocks. Some have damaged leaves, while others grow green and healthy. What they all have in common is: They are supplied with water and nutrients in a controlled manner via thin white pipes. Some are given de-icing salt, which is also spread on Berlin’s streets in winter to reduce the risk of slipping.

More than half of Berlin’s street trees are damaged

Above all, lime and maple, the most common street trees in Berlin, absorb the de-icing salt through their roots and store it. “In the summer months, especially when it is very dry, this leads to necrotic damage. The trees suffer and shed their leaves prematurely,” explains Claus Bull. “It’s a little like us humans: If we eat a lot of pretzel sticks but don’t drink anything with them, we don’t feel well either.”

The approximately 430,000 Berlin street trees perform an important task in the city as natural air conditioning: They provide shade, filter the air, produce oxygen, keep the water in the spaces between the roots – and ensure that we also feel comfortable in large avenues such as Unter den Linden and on otherwise concrete squares. But the side effects of climate change, such as droughts and heavy rain, and everyday city stress, such as high levels of radiation, air pollution, dog urine, soil sealing or de-icing salts, cause problems for the trees. According to the Berlin street tree status report from 2020 (German only), more than half of all street trees in the city are now slightly or severely damaged. The trees studied were lime, maple, horse chestnut and sycamore, which together make up more than three quarters of the tree population in Berlin’s city centre. “The trees in the city have a lot to put up with” They are our service providers,” says Claus Bull.

In order to find out how much water and nutrients urban trees need to be supplied with during a vegetation period so that they can continue to live well despite de-icing salts, Claus Bull and Dirk Jäger carried out the “Fertilisation and Irrigation of Berlin Street Trees” (DuBeBa) project in 2016. On the Hohenzollerndamm, Norway maple trees were fed a nutrient solution containing potassium and magnesium from May to September via drip hoses laid beneath the turf. A comparison group of trees was not supplied. The amount of liquid supplied was calculated using up-to-date data from the weather station on the BHT campus. The pleasing result: “By means of targeted fertilisation and irrigation, we were able to reduce the necrosis on the leaves of the trees by a third and therefore demonstrably vitalise the trees,” explains Dirk Jäger. “That was an incentive for us to keep going.”

Research objective: to keep the trees healthy in the long term

Since then, students have been investigating how urban trees react to changing environmental conditions under laboratory conditions in the BHT greenhouse as part of courses and bachelor theses. The tree for the test is the small-leaved lime – one of the oldest Berlin city trees. In order to keep measurement errors as low as possible, the scientists use genetically identical tree clones that were propagated using cuttings. “We want to understand what actually happens in the plant when we add ballast salts such as sodium chloride – also in combination with potassium. How much water and nutrients does it need to be supplied with in order to remain vitalised?” says Dirk Jäger. “It is also exciting for us to find genetic variations that make the trees tolerant to certain pollutants or make them better able to withstand periods of drought. Our goal is to prevent damage to the trees in the long term.” Street tree species that are also planted in Berlin, such as sycamores or robinia, which is considered invasive, are more resistant to environmental influences such as de-icing salt. However, they bring other disadvantages, including diseases and pests. “Sycamores, for example, protrude heavily into the light profile of the streets and have an enormous amount of leaf fall,” explains Claus Bull. “Fungal diseases are also very difficult for them to cope with.”

Berlin has several thousand outdoor laboratories

Berlin offers an ideal research environment for Claus Bull, Dirk Jäger and the entire laboratory team in the greenhouse of the Horticultural Phytotechnology course. “The city is big. With the many green spaces, parks and large main roads, we find the entire spectrum of site conditions for street trees here,” says Claus Bull and adds, “The initial genetic situation in Berlin is also excellent for our research – we have several thousand outdoor laboratories right on our doorstep.”

The two researchers do not assume that the results of their urban tree research will improve the situation of Berlin’s urban trees in the short term. However, it is much more important to prioritise the topic of urban tree fertilisation and irrigation in the city, as Claus Bull emphasises. “This also requires politically correct decisions, for example in questions of urban planning and the provision of funds for the green space authorities. In order to improve the living conditions of trees in Berlin’s green spaces and along the streets, the team is in contact with the Berlin Rainwater Agency, which advises and supports administrations, housing companies and property owners in using rainwater as a resource for the city. The course is also closely networked with the Berlin tree nursery sector. Above all, however, Claus Bull, Dirk Jäger and their colleagues want to sensitise students to the increasing stress that street trees in the city are exposed to. “We want to encourage critical thinking,” says Claus Bull. “The students should learn to question processes and to consider how the scarce resource of water in a city like Berlin can be grouped or used in other ways – in order to derive clever solutions from it later.” (vdo)

Further information

- Phytotechnology in Horticulture (B. Sc. at the BHT)

- Facts and figures on Berlin’s urban trees (Senate Department for Mobility, Transport, Climate Protection and the Environment), German only

- Donations for city trees: Urban tree campaign of the Senate Department for Mobility, Transport, Climate Protection and Environment, German only

- Initiative “Gieß den Kiez” (“Water the neighbourhood”), German only

More Stories

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

©SPB_Pedro Bacerra (Monika Staesche); © Charlot van Heeswijk (Dorothea Winter); © GSCN / Arne Sattler (Sina Bartfeld); © Prof. Dr. Petra Mund

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWomen shaping science: Perspectives from Berlin's research landscape on International Women's Day.→

©SPB_Pedro Bacerra (Monika Staesche); © Charlot van Heeswijk (Dorothea Winter); © GSCN / Arne Sattler (Sina Bartfeld); © Prof. Dr. Petra Mund

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWomen shaping science: Perspectives from Berlin's research landscape on International Women's Day.→Women shaping science: Perspectives from Berlin's research landscape on International Women's Day

-

Insights Facts & Events

© Bundespreis Ecodesign. Urheber/in: IDZ Berlin

Insights Facts & Events“Mach Moor - Design with Paludiculture”: An Exhibition on Peatland Protection in Berlin→

© Bundespreis Ecodesign. Urheber/in: IDZ Berlin

Insights Facts & Events“Mach Moor - Design with Paludiculture”: An Exhibition on Peatland Protection in Berlin→“Mach Moor - Design with Paludiculture”: An Exhibition on Peatland Protection in Berlin

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Nikolaus Brade

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the project “Multisensory in Dialogue and Artistic Practice”, UdK Berlin and Folkwang are sending a strong signal for the future of artistic…→

© Nikolaus Brade

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the project “Multisensory in Dialogue and Artistic Practice”, UdK Berlin and Folkwang are sending a strong signal for the future of artistic…→Unlocking Joint Potential

-

Transfer – Stories

© Shutterstock / Studio Romantic

Transfer – StoriesCan elderly people regain independence through targeted exercise? Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Uwe Bettig of ASH Berlin examined this question in…→

© Shutterstock / Studio Romantic

Transfer – StoriesCan elderly people regain independence through targeted exercise? Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Uwe Bettig of ASH Berlin examined this question in…→Fit for home again

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Agentur Medienlabor / Stefan Schubert

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesFive companies from the capital region were honoured for their visionary ideas and products, and another received a special award.→

© Agentur Medienlabor / Stefan Schubert

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesFive companies from the capital region were honoured for their visionary ideas and products, and another received a special award.→Berlin Brandenburg Innovation Award 2025 – The Winners

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© TU Berlin/Felix Noak

Insights Transfer – StoriesProf. Dr. Giuseppe Caire, at TU Berlin, is working on a new transmission method that could revolutionize wireless communication completely.→

© TU Berlin/Felix Noak

Insights Transfer – StoriesProf. Dr. Giuseppe Caire, at TU Berlin, is working on a new transmission method that could revolutionize wireless communication completely.→Rethinking Wireless Communication

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesIn January 2025, the European University Alliance EUonAIR was launched. More about this unique alliance tells us Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr.…→

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesIn January 2025, the European University Alliance EUonAIR was launched. More about this unique alliance tells us Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr.…→"We don't want to reinvent the wheel”

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Christian Kielmann

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesEurope’s largest laboratory infrastructure for transfer teams in the field of Green Chemistry is being built on the campus of TU Berlin. The “Chemical…→

© Christian Kielmann

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesEurope’s largest laboratory infrastructure for transfer teams in the field of Green Chemistry is being built on the campus of TU Berlin. The “Chemical…→Construction Kick-off: „Chemical Invention Factory“

-

Insights

© WISTA.Plan GmbH / Dirk Laubner

InsightsHow can a quarter such as the Adlershof Science and Technology Park be made climate-resilient and thus future-proof? WISTA Management GmbH is…→

© WISTA.Plan GmbH / Dirk Laubner

InsightsHow can a quarter such as the Adlershof Science and Technology Park be made climate-resilient and thus future-proof? WISTA Management GmbH is…→Blueprint for the Future

-

Insights Facts & Events

© Matters of Activity / HU Berlin

Insights Facts & EventsOn 19 September, the Cluster of Excellence ‘Matters of Activity’ will hold its final annual conference. Brain City interview with Dr Christian Stein.→

© Matters of Activity / HU Berlin

Insights Facts & EventsOn 19 September, the Cluster of Excellence ‘Matters of Activity’ will hold its final annual conference. Brain City interview with Dr Christian Stein.→“We bring the material to eye level”

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© TU Berlin / allefarben-foto

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesDrone logistics, recycling of building material and wastewater reuse: these ideas are to be tested in so-called “Reallaboren” (Real-World…→

© TU Berlin / allefarben-foto

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesDrone logistics, recycling of building material and wastewater reuse: these ideas are to be tested in so-called “Reallaboren” (Real-World…→Three Real-World Laboratories are being Launched in Berlin

-

Insights

© Jens Freudenberg

InsightsInterview with Prof. Cordula Endter, Professor of Social Work in the Digitalised Society at the Katholische Hochschule Berlin.→

© Jens Freudenberg

InsightsInterview with Prof. Cordula Endter, Professor of Social Work in the Digitalised Society at the Katholische Hochschule Berlin.→Beyond Needs Assessments – Co-Creation as a User-Centered Development Paradigm

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Stefan Klenke / HU Berlin

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesBerlin-based battery researcher Prof. Dr. Philipp Adelhelm has been awarded the 2024 Berlin Science Award. Prof. Dr. Inka Mai from TU Berlin received…→

© Stefan Klenke / HU Berlin

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesBerlin-based battery researcher Prof. Dr. Philipp Adelhelm has been awarded the 2024 Berlin Science Award. Prof. Dr. Inka Mai from TU Berlin received…→Prof. Dr. Philipp Adelhelm honored with Berlin Science Award

-

Insights Facts & Events

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Insights Facts & EventsIt's all about future food production: in the CUBES Circle project, scientists are researching how established agricultural production systems can be…→

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Insights Facts & EventsIt's all about future food production: in the CUBES Circle project, scientists are researching how established agricultural production systems can be…→Tomatoes and fish in a zero-waste cycle

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Gorodenkoff / Shutterstock.com

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview: Prof. Dr. Petra Ritter gives an insight into the cross-border project TEF-Health.→

© Gorodenkoff / Shutterstock.com

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview: Prof. Dr. Petra Ritter gives an insight into the cross-border project TEF-Health.→European test infrastructure for AI in healthcare

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe KI-Werkstatt at the HTW Berlin brings together the university’s expertise in an interdisciplinary manner to research the practical use of AI.→

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe KI-Werkstatt at the HTW Berlin brings together the university’s expertise in an interdisciplinary manner to research the practical use of AI.→Strengthening generative AI in research and teaching

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© DLR (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWith the newly founded institute, the German Aerospace Center is pooling its expertise in the field of space instruments and space research in Brain…→

© DLR (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWith the newly founded institute, the German Aerospace Center is pooling its expertise in the field of space instruments and space research in Brain…→New DLR Institute of Space Research

-

Startup Transfer – Stories

© theion

Startup Transfer – StoriesThe start-up theion wants to revolutionise the battery market and accelerate the energy transition with a new technology in Brain City Berlin.→

© theion

Startup Transfer – StoriesThe start-up theion wants to revolutionise the battery market and accelerate the energy transition with a new technology in Brain City Berlin.→“Batteries made in Germany, made in Berlin”

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Berlin University Alliance / Stefan Klenke

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the innovate! lab, the Berlin University Alliance (BUA) aims to bring cutting-edge research into practice quickly and purposefully. Dr.…→

© Berlin University Alliance / Stefan Klenke

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the innovate! lab, the Berlin University Alliance (BUA) aims to bring cutting-edge research into practice quickly and purposefully. Dr.…→“Research transfer through agility”

-

Insights

© FlorianWehde / Unsplash; JohnCairns /Oxford-University

InsightsThe Oxford Berlin Research Partnership brings together top researchers and provides targeted support for talented young scientists.→

© FlorianWehde / Unsplash; JohnCairns /Oxford-University

InsightsThe Oxford Berlin Research Partnership brings together top researchers and provides targeted support for talented young scientists.→Building bridges between Oxford and Berlin

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Berlin Partner / eventfotografen.berlin

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesOn March 4, a total of 19 universities, colleges and non-university research institutions signed the statutes of UNITE Sciences e.V.→

© Berlin Partner / eventfotografen.berlin

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesOn March 4, a total of 19 universities, colleges and non-university research institutions signed the statutes of UNITE Sciences e.V.→UNITE Sciences: Accelerating technology transfer

-

Insights Innovations

© Berlin Institute for Innovation

Insights Innovations“Innovation = Invention + Market Penetration” is the working formula of the Berlin Institute for Innovation. The team takes a scientifically sound…→

© Berlin Institute for Innovation

Insights Innovations“Innovation = Invention + Market Penetration” is the working formula of the Berlin Institute for Innovation. The team takes a scientifically sound…→The Research Manufactory

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

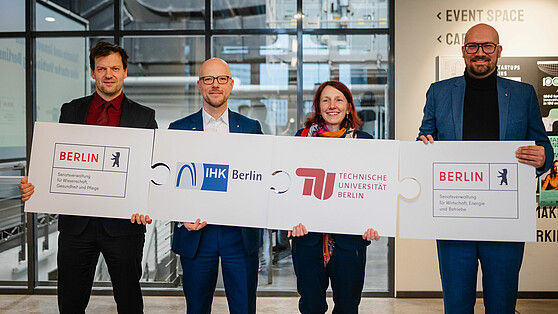

© IHK Berlin

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesTU Berlin and IHK Berlin want to work closely together to promote university spin-offs and innovation in Brain City Berlin. An agreement has now been…→

© IHK Berlin

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesTU Berlin and IHK Berlin want to work closely together to promote university spin-offs and innovation in Brain City Berlin. An agreement has now been…→Cooperation agreement between TU Berlin and IHK Berlin signed

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© BettaF!sh/Valentin Pellio

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe start-up BettaF!sh develops and produces the world's first authentic seaweed-based fish alternatives in Brain City Berlin.→

© BettaF!sh/Valentin Pellio

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe start-up BettaF!sh develops and produces the world's first authentic seaweed-based fish alternatives in Brain City Berlin.→“We are breaking new ground with everything we do”

-

Insights

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

InsightsEvery year, sweet treats beckon at Christmas. Why is ist so hard for us to resist them? Prof Dr Soyoung Q Park knows more about this.→

© Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

InsightsEvery year, sweet treats beckon at Christmas. Why is ist so hard for us to resist them? Prof Dr Soyoung Q Park knows more about this.→Christmas dinner: no surprises, please!

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Berlin Partner/Eventfotografen

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe research landscape in Berlin and Brandenburg is excellent but quite fragmented. The UNITE consortium aims to change that.→

© Berlin Partner/Eventfotografen

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe research landscape in Berlin and Brandenburg is excellent but quite fragmented. The UNITE consortium aims to change that.→UNITE: Fostering Synergies, Accelerating Innovations

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Berlin Partner

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesThe fourth Transfer Week Berlin-Brandenburg from November 25 to 29 will focus on the latest developments in regional transfer activities. 62 partner…→

© Berlin Partner

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesThe fourth Transfer Week Berlin-Brandenburg from November 25 to 29 will focus on the latest developments in regional transfer activities. 62 partner…→The future of knowledge transfer: Transfer Week 2024

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

CCC © Michael Reinhardt

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview with Dr. Anita Dame, Managing Director of the Climate Change Center Berlin Brandenburg.→

CCC © Michael Reinhardt

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview with Dr. Anita Dame, Managing Director of the Climate Change Center Berlin Brandenburg.→“Climate transformation is a marathon”

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© CeRRI 2024

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesTransfer activities and research do not compete with each other. On the contrary! This is one of the key findings of the “Transfer 1000” study…→

© CeRRI 2024

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesTransfer activities and research do not compete with each other. On the contrary! This is one of the key findings of the “Transfer 1000” study…→„Transfer 1000“: Study on science transfer

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© edelviz

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview with Lia Carlucci, Managing Director of the Food Campus Berlin. She tells us more about the current status of the project - and…→

© edelviz

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview with Lia Carlucci, Managing Director of the Food Campus Berlin. She tells us more about the current status of the project - and…→“Collaboration instead of competition”

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© HTW/ZfS

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesClimate, health and sustainability – these are the main topics of Transferale. From 25 to 27 September, the science and transfer festival will be held…→

© HTW/ZfS

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesClimate, health and sustainability – these are the main topics of Transferale. From 25 to 27 September, the science and transfer festival will be held…→Ideas for Berlin’s future

-

Insights

© Shutterstock / Andrii Yalanskyi

InsightsCommunicating science in a way that is relevant to everyday life and easy to understand – that is the approach of Prof. Dr. Sascha Friesike. The Brain…→

© Shutterstock / Andrii Yalanskyi

InsightsCommunicating science in a way that is relevant to everyday life and easy to understand – that is the approach of Prof. Dr. Sascha Friesike. The Brain…→“Science must be able to explain what it does”

-

Startup Transfer – Stories

© STOFF2/Kerstin Reisch

Startup Transfer – StoriesBerlin Start-up STOFF2 wants to bring the ‘Zinc Intermediate-step Electrolyser’ (ZZE) to market maturity and is working closely with the TU Berlin to…→

© STOFF2/Kerstin Reisch

Startup Transfer – StoriesBerlin Start-up STOFF2 wants to bring the ‘Zinc Intermediate-step Electrolyser’ (ZZE) to market maturity and is working closely with the TU Berlin to…→The small, subtle intermediate step

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© WISTA Management GmbH – www.adlershof.de

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe Adlershof Science and Technology Park is the largest of Berlin’s eleven future locations. The close connection between science and business has…→

© WISTA Management GmbH – www.adlershof.de

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe Adlershof Science and Technology Park is the largest of Berlin’s eleven future locations. The close connection between science and business has…→“We thrive on proximity and exchange”

-

Insights

© Neurospace

InsightsThe start-up Neurospace stands like no other for the booming “New Space” industry in Brain City Berlin. An interview with Irene Selvanathan, founder…→

© Neurospace

InsightsThe start-up Neurospace stands like no other for the booming “New Space” industry in Brain City Berlin. An interview with Irene Selvanathan, founder…→“We want to take science and industry to the moon”

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Berlin Partner

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe “Additive Manufacturing Berlin Brandenburg” (AMBER) cluster aims to accelerate the transfer of results from cutting-edge research into…→

© Berlin Partner

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe “Additive Manufacturing Berlin Brandenburg” (AMBER) cluster aims to accelerate the transfer of results from cutting-edge research into…→AMBER: Networking cutting-edge research and industry

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Kai Müller Photography

Insights Transfer – StoriesA newspaper interview provided the impetus for founding the start-up. Brain City interview with airpuls founder Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Slawomir…→

© Kai Müller Photography

Insights Transfer – StoriesA newspaper interview provided the impetus for founding the start-up. Brain City interview with airpuls founder Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Slawomir…→airpuls: 5G solutions from research

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

Shutterstock © optimarc

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith a new transfer certificate, the TU Berlin certifies practical skills for students who have dealt with methods and issues of knowledge and…→

Shutterstock © optimarc

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith a new transfer certificate, the TU Berlin certifies practical skills for students who have dealt with methods and issues of knowledge and…→Thinking outside the box

-

Insights Transfer – Stories Innovations

© Berlin Partner

Insights Transfer – Stories InnovationsQuantum technology is considered to be the next big technological leap. The Brain City Berlin offers ideal conditions for this.→

© Berlin Partner

Insights Transfer – Stories InnovationsQuantum technology is considered to be the next big technological leap. The Brain City Berlin offers ideal conditions for this.→BERLIN QUANTUM: a new initiative for quantum technologies

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

Design © Sarah Engler; Foto © Alexander Bob

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview with Prof. Dr. Uwe Bettig. As Professor of Management and Business Administration at ASH Berlin, he heads the IFAF project…→

Design © Sarah Engler; Foto © Alexander Bob

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City Interview with Prof. Dr. Uwe Bettig. As Professor of Management and Business Administration at ASH Berlin, he heads the IFAF project…→Many creative ideas and approaches

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Ivar Veermae

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt EINS in Berlin-Charlottenburg, the TU Berlin supports start-ups that meet global challenges sustainably in three ways. Universities and colleges…→

© Ivar Veermae

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt EINS in Berlin-Charlottenburg, the TU Berlin supports start-ups that meet global challenges sustainably in three ways. Universities and colleges…→Economical, ecological, social

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

TU Berlin © Felix Noak

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesInterdisciplinary research teams have until 29 April to submit their proposals for the Next Grand Challenge initiative of the Berlin University…→

TU Berlin © Felix Noak

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesInterdisciplinary research teams have until 29 April to submit their proposals for the Next Grand Challenge initiative of the Berlin University…→Next Grand Challenge: apply now!

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Alfred-Wegener-Institut/Micheal Gutsche (CC-BY 4.0)

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesA special exhibition at the Deutsches Technikmuseum makes things crystal clear: There is little time left to save the Arctic.→

© Alfred-Wegener-Institut/Micheal Gutsche (CC-BY 4.0)

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesA special exhibition at the Deutsches Technikmuseum makes things crystal clear: There is little time left to save the Arctic.→Exhibition tip: “Thin ice”

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Zukunftsorte Berlin

Insights Transfer – StoriesAn interview with Brain City Ambassador Steffen Terberl, Head of the Zukunftsorte Berlin office.→

© Zukunftsorte Berlin

Insights Transfer – StoriesAn interview with Brain City Ambassador Steffen Terberl, Head of the Zukunftsorte Berlin office.→“So that innovation history can be written in Berlin again”

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

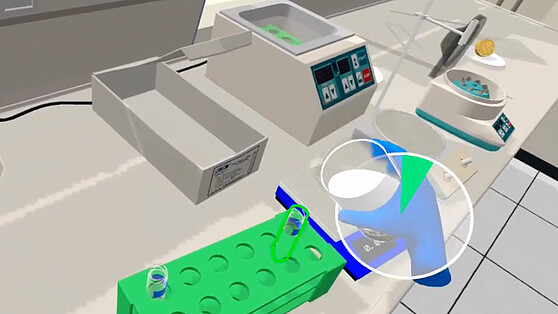

© BHT-MINT-VR-Labs

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt the MINT VR labs at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik, an interdisciplinary team works on didactic concepts for virtual laboratories and…→

© BHT-MINT-VR-Labs

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt the MINT VR labs at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik, an interdisciplinary team works on didactic concepts for virtual laboratories and…→Learning through play in the virtual bio-lab

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© BPWT

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWith an all-day kick-off conference in the stilwerk KantGaragen, the Transfer Week Berlin-Brandenburg 2023 starts. From 20 to 24 November, the event…→

© BPWT

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWith an all-day kick-off conference in the stilwerk KantGaragen, the Transfer Week Berlin-Brandenburg 2023 starts. From 20 to 24 November, the event…→“Science x Business”: Transfer Week 2023

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© edelVIZ

Insights Transfer – StoriesFrom 2024, the Food Campus Berlin is due to be built in Berlin’s industrial Tempelhof-Ost region. The Science Park will be focussing on nutrition and…→

© edelVIZ

Insights Transfer – StoriesFrom 2024, the Food Campus Berlin is due to be built in Berlin’s industrial Tempelhof-Ost region. The Science Park will be focussing on nutrition and…→Think Tank for the food of the future

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Berlin Partner/Wüstenhagen

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe focus is on the science location, the science and technology transfer that is characteristic of Berlin – and of course the Brain City Ambassadors.…→

© Berlin Partner/Wüstenhagen

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe focus is on the science location, the science and technology transfer that is characteristic of Berlin – and of course the Brain City Ambassadors.…→Brain City Berlin launches new campaign motifs

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Falling Walls Foundation

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesBerlin Science Week is back from November 1 to 10. New this year: The ART & SCIENCE FORUM at Holzmarkt 25 is the central location of the science…→

© Falling Walls Foundation

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesBerlin Science Week is back from November 1 to 10. New this year: The ART & SCIENCE FORUM at Holzmarkt 25 is the central location of the science…→With a focus on art & science: Berlin Science Week 2023

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Peter Himsel/Campus Berlin-Buch GmbH

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesBrain City Berlin has a new start-up centre: The BerlinBioCube on the Campus Berlin-Buch includes 8,000 square metres of modern laboratory and office…→

© Peter Himsel/Campus Berlin-Buch GmbH

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesBrain City Berlin has a new start-up centre: The BerlinBioCube on the Campus Berlin-Buch includes 8,000 square metres of modern laboratory and office…→The BerlinBioCube is open

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Gisma

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe Gisma University of Applied Sciences has had a campus in the Brain City Berlin since 2017. More than 660 students from all over the world are…→

© Gisma

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe Gisma University of Applied Sciences has had a campus in the Brain City Berlin since 2017. More than 660 students from all over the world are…→Giving impulses to the economy

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© HU Berlin

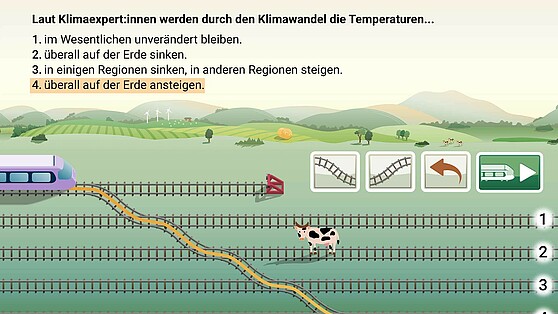

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories“TRAIN 4 Science” encourages children, but also adults, to deal with climate change in a playful way. The app was developed in the Brain City Berlin…→

© HU Berlin

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories“TRAIN 4 Science” encourages children, but also adults, to deal with climate change in a playful way. The app was developed in the Brain City Berlin…→On the virtual train to a sustainable future

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt the business and science location Berlin Schöneweide, tradition meets the ideas and solutions of tomorrow. The scientific nucleus of the area: the…→

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesAt the business and science location Berlin Schöneweide, tradition meets the ideas and solutions of tomorrow. The scientific nucleus of the area: the…→A place of innovation and transformation

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© LAS Art Foundation/Juan Camilo Roan

Insights Transfer – Stories‘Pollinator Pathmaker’ is the name given to the living work of art that is currently flowering, buzzing and fluttering in front of the Museum für…→

© LAS Art Foundation/Juan Camilo Roan

Insights Transfer – Stories‘Pollinator Pathmaker’ is the name given to the living work of art that is currently flowering, buzzing and fluttering in front of the Museum für…→Garden art from an insect’s perspective

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe project "Zukunft findet Stadt - Hochschulnetzwerk für ein resilientes Berlin" is something that is so far unique for Berlin. Project leader Prof.…→

© HTW Berlin/Alexander Rentsch

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe project "Zukunft findet Stadt - Hochschulnetzwerk für ein resilientes Berlin" is something that is so far unique for Berlin. Project leader Prof.…→"We want innovations that are created in Berlin to be implemented here"

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© BHT/Zarko Martovic

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesOn 17 June, more than 60 scientific and science-related institutions in the Brain City Berlin and Potsdam will open their doors for the “Long Night of…→

© BHT/Zarko Martovic

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesOn 17 June, more than 60 scientific and science-related institutions in the Brain City Berlin and Potsdam will open their doors for the “Long Night of…→Lange Nacht der Wissenschaften 2023

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© BSBI

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesOn 24 June the AI scene will meet in Berlin-Neukölln. The “1st International Conference on Artificial Intelligence” at the BSBI is primarily about the…→

© BSBI

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesOn 24 June the AI scene will meet in Berlin-Neukölln. The “1st International Conference on Artificial Intelligence” at the BSBI is primarily about the…→AI Conference at the Berlin School of Business & Innovation

-

Startup Transfer – Stories

© Quantistry

Startup Transfer – StoriesThe Berlin start-up Quantistry makes chemical experiments in digital space possible with the help of Artificial Intelligence and quantum chemical…→

© Quantistry

Startup Transfer – StoriesThe Berlin start-up Quantistry makes chemical experiments in digital space possible with the help of Artificial Intelligence and quantum chemical…→The chemistry lab in the cloud

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Hallbauer & Fioretti

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview: Prof. Dr. Emmanuelle Charpentier, Nobel Laureate and Managing Director of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens.→

© Hallbauer & Fioretti

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview: Prof. Dr. Emmanuelle Charpentier, Nobel Laureate and Managing Director of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens.→"Basic research is the basis for innovation"

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© BVG/Andreas Süß

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWhat does an electric bus sound like? Lukas Esser, a student at Berlin University of the Arts, has developed the new sound for Germany’s electric…→

© BVG/Andreas Süß

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWhat does an electric bus sound like? Lukas Esser, a student at Berlin University of the Arts, has developed the new sound for Germany’s electric…→Electric sound of the future

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© ASH Berlin/Cristián Pérez

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe acronym SAGE, in German stands for Social Work, Health, Education and Training. Prof. Bettina Völter, Rector at the ASH Berlin, tells us more…→

© ASH Berlin/Cristián Pérez

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe acronym SAGE, in German stands for Social Work, Health, Education and Training. Prof. Bettina Völter, Rector at the ASH Berlin, tells us more…→SAGE – a social three-way alliance

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Maschinenraum

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesThe University of Applied Sciences wants to tap additional transfer potential by means of cooperation with the nationwide network of SMEs.→

© Maschinenraum

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesThe University of Applied Sciences wants to tap additional transfer potential by means of cooperation with the nationwide network of SMEs.→HTW Berlin cooperates with Maschinenraum

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© QAH

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe "Zukunftsort" Technology Park Humboldthain represents the heyday of Berlin’s industrial history, but also stands for successful synergies between…→

© QAH

Insights Transfer – StoriesThe "Zukunftsort" Technology Park Humboldthain represents the heyday of Berlin’s industrial history, but also stands for successful synergies between…→Tradition meets innovation

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Stefan Schostok

Insights Transfer – StoriesA guest article from Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Selin Arikoglu, Professor of child and youth welfare at the Catholic University of Applied Social…→

© Stefan Schostok

Insights Transfer – StoriesA guest article from Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Selin Arikoglu, Professor of child and youth welfare at the Catholic University of Applied Social…→Giving a scientific voice to the relatives of prisoners

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Berlin Partner

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWith a new image film Brain City Berlin starts the year 2023. Our Brain City Ambassadors are the protagonists of the video.→

© Berlin Partner

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesWith a new image film Brain City Berlin starts the year 2023. Our Brain City Ambassadors are the protagonists of the video.→“We are Brain City Berlin”

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© HWR Berlin/ Franziska Ihle

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the project “KlinKe”, Prof. Dr. Silke Bustamante and her colleague Prof. Dr. Andrea Pelzeter at the HWR Berlin are researching which of the…→

© HWR Berlin/ Franziska Ihle

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the project “KlinKe”, Prof. Dr. Silke Bustamante and her colleague Prof. Dr. Andrea Pelzeter at the HWR Berlin are researching which of the…→On the way to becoming a climate-neutral hospital

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Transfer Week

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesFrom 21 to 25 November, scientists can once again discuss future-oriented topics on a practical level together with companies from Berlin and…→

© Transfer Week

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesFrom 21 to 25 November, scientists can once again discuss future-oriented topics on a practical level together with companies from Berlin and…→Providing impulses for cooperation: Transfer Week 2022

-

Facts & Events Transfer – Stories

© Falling Walls Foundation

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesAn interview with Christine Brummer, director of Berlin Science Week.→

© Falling Walls Foundation

Facts & Events Transfer – StoriesAn interview with Christine Brummer, director of Berlin Science Week.→Opening up science for dialogue with society

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

Shutterstock © Monster Ztudio

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the help of Artificial Intelligence, the research project “news-polygraph”, anchored in the Brain City Berlin, aims to identify manipulated media…→

Shutterstock © Monster Ztudio

Insights Transfer – StoriesWith the help of Artificial Intelligence, the research project “news-polygraph”, anchored in the Brain City Berlin, aims to identify manipulated media…→“news-polygraph”: Funding by the BMBF

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

© Felix Noak

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview with Dr. phil. Thorsten Philipp, Advisor Transdisciplinary Teaching in the Office of the Vice Presidents of TU Berlin.→

© Felix Noak

Insights Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview with Dr. phil. Thorsten Philipp, Advisor Transdisciplinary Teaching in the Office of the Vice Presidents of TU Berlin.→“Everybody knows something”

-

Insights Transfer – Stories

@ Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Insights Transfer – StoriesListening to sounds like the bat: On "Sound Walk" with Hannes Hoelzl, sound artist and lecturer for Generative Arts/Computational Arts at the UdK…→

@ Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Insights Transfer – StoriesListening to sounds like the bat: On "Sound Walk" with Hannes Hoelzl, sound artist and lecturer for Generative Arts/Computational Arts at the UdK…→Seeing with the Ears

-

Insights

Photo (private)

InsightsGuest article by Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Rainer Zeichhardt, Professor for General Business Administration at the BSP – Business & Law School…→

Photo (private)

InsightsGuest article by Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Rainer Zeichhardt, Professor for General Business Administration at the BSP – Business & Law School…→New Work – new working concepts for sustainable corporate cultures

-

Transfer – Stories

Image: Shutterstock © Yurchanka Siarhei

Transfer – StoriesThe Berlin AI Competence Centre BIFOLD will receive 22 million Euro annually in the future from the Federal government and the State of Berlin.→

Image: Shutterstock © Yurchanka Siarhei

Transfer – StoriesThe Berlin AI Competence Centre BIFOLD will receive 22 million Euro annually in the future from the Federal government and the State of Berlin.→Millions in Funding for AI Research in Berlin

-

Transfer – Stories

Falling Walls Foundation © Judith Schalansky

Transfer – StoriesFrom November 1st through the 10th, the scientific world comes together again in Brain City Berlin. Scientific institutions or organisations can still…→

Falling Walls Foundation © Judith Schalansky

Transfer – StoriesFrom November 1st through the 10th, the scientific world comes together again in Brain City Berlin. Scientific institutions or organisations can still…→“Dare to know”: Berlin Science Week 2022

-

Transfer – Stories

EUREF AG©Gasometertour.de

Transfer – StoriesOn the site of the EUREF-Campus in Berlin-Schoeneberg the transfer of knowledge works particularly impressively.→

EUREF AG©Gasometertour.de

Transfer – StoriesOn the site of the EUREF-Campus in Berlin-Schoeneberg the transfer of knowledge works particularly impressively.→Hands-on Energy Transition

-

Transfer – Stories

© SCC Events/Norbert Wilhelmi

Transfer – StoriesInterview with Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Gabriele Mielke, Vice President of the VICTORIA | International University of Applied Sciences and also…→

© SCC Events/Norbert Wilhelmi

Transfer – StoriesInterview with Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Gabriele Mielke, Vice President of the VICTORIA | International University of Applied Sciences and also…→"Major Events Affect Life in the City on Different Levels”

-

Insights

Dr. Anja Sommerfeld (private)/ Dr. Gregor Hofmann (David Ausserhofer)

InsightsBrain City interview with D. Anja Sommerfeld und Dr Gregor Hofmann of Berlin Research 50. The initiative of Berlin’s non-university research…→

Dr. Anja Sommerfeld (private)/ Dr. Gregor Hofmann (David Ausserhofer)

InsightsBrain City interview with D. Anja Sommerfeld und Dr Gregor Hofmann of Berlin Research 50. The initiative of Berlin’s non-university research…→Getting the Best out of Berlin as a Science Hub

-

Transfer – Stories

Photo: Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken (vdo)

Transfer – StoriesThe Charlottenburg Innovation Centre CHIC hosts around 50 start-ups. Situated at Brain City Berlin’s “Zukunftsort” Campus Charlottenburg, the CHIC…→

Photo: Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken (vdo)

Transfer – StoriesThe Charlottenburg Innovation Centre CHIC hosts around 50 start-ups. Situated at Brain City Berlin’s “Zukunftsort” Campus Charlottenburg, the CHIC…→CHIC - Business Incubator at a "Zukunftsort’"

-

Transfer – Stories

Photo: Mall Anders/Matthew Crabbe

Transfer – Stories“Mall Anders” is an open learning laboratory which was launched by the FU Berlin, HU Berlin, TU Berlin and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in a…→

Photo: Mall Anders/Matthew Crabbe

Transfer – Stories“Mall Anders” is an open learning laboratory which was launched by the FU Berlin, HU Berlin, TU Berlin and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in a…→Science in a Shopping Centre

-

Transfer – Stories

BHT/Martin Gasch

Transfer – StoriesInterview: Brain City Ambassador Dr-Ing. Ivo Boblan, Professor of the Humanoid Robotics Study Programme at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik, and…→

BHT/Martin Gasch

Transfer – StoriesInterview: Brain City Ambassador Dr-Ing. Ivo Boblan, Professor of the Humanoid Robotics Study Programme at the Berliner Hochschule für Technik, and…→“Robots Can Save us a Great Deal of Work”

-

Transfer – Stories

(Left to right) Prof. Christian Matzdorf, Police commissioner Turgay Akkaya, Stefan Graf Finck von Finckenstein, Photo: HWR Berlin / Sylke Schumann

Transfer – StoriesPolice commissioner Turgay Akkaya has developed an anti-stalking app as part of his Bachelor’s project at the HWR Berlin. At the beginning of January…→

(Left to right) Prof. Christian Matzdorf, Police commissioner Turgay Akkaya, Stefan Graf Finck von Finckenstein, Photo: HWR Berlin / Sylke Schumann

Transfer – StoriesPolice commissioner Turgay Akkaya has developed an anti-stalking app as part of his Bachelor’s project at the HWR Berlin. At the beginning of January…→A Preventive App Against Stalking

-

Transfer – Stories

(From left to right) Steffen Terberl/FU Berlin; Prof. Dr. Hannes Rothe/ICN Business School, photo: Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Transfer – StoriesIn the BioTech sector, the Berlin region is not making full use of its innovation potential. This is the conclusion of the “Deep Tech Futures Report…→

(From left to right) Steffen Terberl/FU Berlin; Prof. Dr. Hannes Rothe/ICN Business School, photo: Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

Transfer – StoriesIn the BioTech sector, the Berlin region is not making full use of its innovation potential. This is the conclusion of the “Deep Tech Futures Report…→“BioTech does not get up and running on its own”

-

Transfer – Stories

Photo: Christina Lüdtke (private source)

Transfer – StoriesFour universities, one network: The network “Science & Startups” groups the start-up services of the universities united in the Berlin University…→

Photo: Christina Lüdtke (private source)

Transfer – StoriesFour universities, one network: The network “Science & Startups” groups the start-up services of the universities united in the Berlin University…→Wide-ranging Support for University Start-ups

-

Transfer – Stories

Photo: private

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr. Anna Klippstein, professor of finance and Eliyahu Mätzschker, student at Touro College Berlin.→

Photo: private

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr. Anna Klippstein, professor of finance and Eliyahu Mätzschker, student at Touro College Berlin.→The Pandemic and its Impact on the Capital Market

-

Transfer – Stories

Credit: André Bakker

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr Anabel Ternès von Hattburg, Professor for International Business Administration at the SRH…→

Credit: André Bakker

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr Anabel Ternès von Hattburg, Professor for International Business Administration at the SRH…→Getting on Board with Digitality

-

Transfer – Stories

Swen Hutter (Foto: David Ausserhofer), Gesine Höltmann (Foto: Martina Sander)

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Gesine Höltmann, research assistant and Swen Hutter, Deputy Director at the Centre for Civil Society Research.→

Swen Hutter (Foto: David Ausserhofer), Gesine Höltmann (Foto: Martina Sander)

Transfer – StoriesA guest contribution by Gesine Höltmann, research assistant and Swen Hutter, Deputy Director at the Centre for Civil Society Research.→Polarisation and Cohesion in the Corona Crisis: a Look at Civil Society

-

Transfer – Stories

Foto: "Lucid Dream", Elena Kunau and Mariya Yordanova

Transfer – StoriesARTIFICIAL REALITY – VIRTUAL INTELLIGENCE is the name of an exhibition that can be seen from 8 to 12 September as part of Ars Electronica Garden…→

Foto: "Lucid Dream", Elena Kunau and Mariya Yordanova

Transfer – StoriesARTIFICIAL REALITY – VIRTUAL INTELLIGENCE is the name of an exhibition that can be seen from 8 to 12 September as part of Ars Electronica Garden…→Interaction via Emotion

-

Transfer – Stories

Credit: Peter Himsel/Campus Berlin-Buch GmbH

Transfer – StoriesThe Campus Berlin-Buch in the north of Brain City Berlin has grown to become one of Europe’s largest business and research centres for life sciences.→

Credit: Peter Himsel/Campus Berlin-Buch GmbH

Transfer – StoriesThe Campus Berlin-Buch in the north of Brain City Berlin has grown to become one of Europe’s largest business and research centres for life sciences.→A Vibrant Healthcare Network

-

Transfer – Stories

Credit: Markus Krutzik

Transfer – StoriesDr. Markus Krutzik, Head of the Joint Lab Integrated Quantum Sensors (IQS), on the "Wissenschaft trifft Wirtschaft" (Science Meets Business") event…→

Credit: Markus Krutzik

Transfer – StoriesDr. Markus Krutzik, Head of the Joint Lab Integrated Quantum Sensors (IQS), on the "Wissenschaft trifft Wirtschaft" (Science Meets Business") event…→"I am Fascinated by the Possibilities of Quantum Sensors"

-

Transfer – Stories

Foto: ESCP Business School Berlin

Transfer – StoriesWhat to do when distance is suddenly the order of the day? A guest contribution by Dr. René Mauer, Professor of Entrepreneurship und Innovation at…→

Foto: ESCP Business School Berlin

Transfer – StoriesWhat to do when distance is suddenly the order of the day? A guest contribution by Dr. René Mauer, Professor of Entrepreneurship und Innovation at…→Using Whiteboards to Combat Digital Fatigue

-

Transfer – Stories

Credit: Alexander Rentsch/HTW Berlin

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Florian Koch of HTW Berlin brings together science, business and civil society in his research.→

Credit: Alexander Rentsch/HTW Berlin

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Florian Koch of HTW Berlin brings together science, business and civil society in his research.→“Increasing Urbanisation also Creates Opportunities”

-

Transfer – Stories

Credit: Rudolf Grillborzer

Transfer – StoriesGuest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr.-Ing. Onur Günlü, Technische Universität Berlin.→

Credit: Rudolf Grillborzer

Transfer – StoriesGuest contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr.-Ing. Onur Günlü, Technische Universität Berlin.→Exploring the "ultimate limits"

-

Transfer – Stories

Credt: Startup Incubator Berlin

Transfer – StoriesThe Startup Incubator Berlin at the Berlin School of Economics and Law is particularly successful in supporting founder teams – as proved by the fact…→

Credt: Startup Incubator Berlin

Transfer – StoriesThe Startup Incubator Berlin at the Berlin School of Economics and Law is particularly successful in supporting founder teams – as proved by the fact…→“We Bring Ideas to Market”

-

Transfer – Stories

Credit: Mimi Thian on Unsolash

Transfer – StoriesGuest Contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr. Petyo Budakov, University of Europe for Applied Sciences.→

Credit: Mimi Thian on Unsolash

Transfer – StoriesGuest Contribution by Brain City Ambassador Dr. Petyo Budakov, University of Europe for Applied Sciences.→“Proudly presenting Brain City Berlin in 2020”

-

Transfer – Stories

Susanne Plaumann (private)

Transfer – StoriesInterview with Brain City Ambassador Susanne Plaumann M.A., Central women's representative at the Beuth University of Applied Sciences Berlin.→

Susanne Plaumann (private)

Transfer – StoriesInterview with Brain City Ambassador Susanne Plaumann M.A., Central women's representative at the Beuth University of Applied Sciences Berlin.→“Careers are now easier to plan for women scientists”

-

Transfer – Stories

Adi Goldstein auf Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesStadtManufaktur Berlin conceptually unites research projects of the TU Berlin under a single roof. The long-term goal of this “open laboratory…→

Adi Goldstein auf Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesStadtManufaktur Berlin conceptually unites research projects of the TU Berlin under a single roof. The long-term goal of this “open laboratory…→Science in Dialogue with the City

-

Transfer – Stories

Falk Weiß

Transfer – StoriesThe knowledge portal “humboldts17” presents current research on the subject of sustainability and welcomes open dialogue with the general public. The…→

Falk Weiß

Transfer – StoriesThe knowledge portal “humboldts17” presents current research on the subject of sustainability and welcomes open dialogue with the general public. The…→17 Goals for the Future

-

Transfer – Stories

Foto: Olga Makarova privat

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Ambassador Olga Makarova reflects on being a microbiologist during the pandemic, and the urgent need for microbiology literacy in society.→

Foto: Olga Makarova privat

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Ambassador Olga Makarova reflects on being a microbiologist during the pandemic, and the urgent need for microbiology literacy in society.→Guest Contribution: COVID-19 and microbiology literacy

-

Transfer – Stories

HIIG

Transfer – StoriesBrain City-Interview with Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schulz, Research Director at the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society (HIIG).→

HIIG

Transfer – StoriesBrain City-Interview with Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schulz, Research Director at the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society (HIIG).→“A sustainable goal of our work is to make clear what the technology can actually do”

-

Transfer – Stories

HTW Berlin

Transfer – StoriesAn interview with Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Kai Reinhardt. On October 28, he will be speaking at the second SpreeTalk at HTW University of…→

HTW Berlin

Transfer – StoriesAn interview with Brain City Ambassador Prof. Dr. Kai Reinhardt. On October 28, he will be speaking at the second SpreeTalk at HTW University of…→“The pandemic has been a catalyst for digitalization”

-

Transfer – Stories

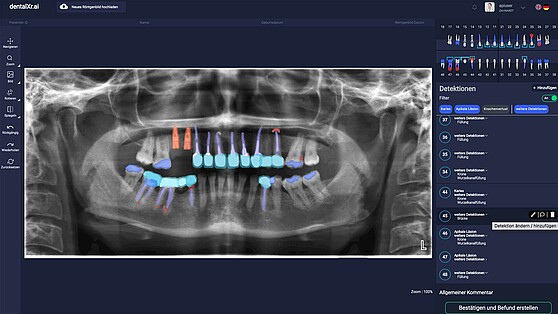

dentalXr.ai

Transfer – StoriesdentalXrai is the first dental start-up to be spun off the Charité. It was launched via the accelerator of the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). We…→

dentalXr.ai

Transfer – StoriesdentalXrai is the first dental start-up to be spun off the Charité. It was launched via the accelerator of the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). We…→Artificial intelligence in the fight against tooth decay

-

Transfer – Stories

Anna Raysyan (private)

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Ambassador Anna Raysyan has been living in Berlin for 3,5 years now. She is a PhD student at the Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und…→

Anna Raysyan (private)

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Ambassador Anna Raysyan has been living in Berlin for 3,5 years now. She is a PhD student at the Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und…→Guest Contribution: “Berlin likes the bold!”

-

Transfer – Stories

©Berlin Partner für Wirtschaft und Technologie

Transfer – StoriesMany top-class researchers and scientists are being attracted to Brain City Berlin every year. The Dual Career Network Berlin helps partners of…→

©Berlin Partner für Wirtschaft und Technologie

Transfer – StoriesMany top-class researchers and scientists are being attracted to Brain City Berlin every year. The Dual Career Network Berlin helps partners of…→Dual Career Network Berlin: getting a good start in Berlin

-

Transfer – Stories

©Matthias Picket

Transfer – StoriesDr. Anne Schreiter, Managing Director of the German Scholars Organization (GSO), reveals in the Brain City interview what alternative career…→

©Matthias Picket

Transfer – StoriesDr. Anne Schreiter, Managing Director of the German Scholars Organization (GSO), reveals in the Brain City interview what alternative career…→"Science is not just about research"

-

Transfer – Stories

© Pocky Lee on Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesMatches in front of empty stadiums, virtual marathons, and many postponed events. Brain City Ambassador Professor Gabriele Mielke is tracking the…→

© Pocky Lee on Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesMatches in front of empty stadiums, virtual marathons, and many postponed events. Brain City Ambassador Professor Gabriele Mielke is tracking the…→"Now is the time for innovators"

-

Transfer – Stories

© AW Creative on Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesJuggling a degree course or teaching with the extra burden of the care of children or other family members is not an easy task. Both students and…→

© AW Creative on Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesJuggling a degree course or teaching with the extra burden of the care of children or other family members is not an easy task. Both students and…→From “Zoo School” to “Maternity Protection”: family-friendly universities

-

Transfer – Stories

© HTW Berlin / Nikolas Fahlbusch

Transfer – StoriesTeaching is currently only taking place online. Guest author Dr Dorothee Haffner, professor for Museology at HTW Berlin - University of Applied…→

© HTW Berlin / Nikolas Fahlbusch

Transfer – StoriesTeaching is currently only taking place online. Guest author Dr Dorothee Haffner, professor for Museology at HTW Berlin - University of Applied…→Guest contribution: "Online teaching is more engaging than I thought"

-

Transfer – Stories

Franziska Sattler

Transfer – StoriesIn the interview: Brain City ambassador Franziska Sattler on her series of events "Kaffeeklatsch mit Wissenschaft" (Talking Science over Coffee) at…→

Franziska Sattler

Transfer – StoriesIn the interview: Brain City ambassador Franziska Sattler on her series of events "Kaffeeklatsch mit Wissenschaft" (Talking Science over Coffee) at…→"Science needs the trust of society"

-

Transfer – Stories

Fotocredit: Ortner & Ortner / Siemens

Transfer – StoriesSiemensstadt 2.0 is a place of the future. The Berlin Senate has approved 9.9 million euros for the first research project "Electrical Drive…→

Fotocredit: Ortner & Ortner / Siemens

Transfer – StoriesSiemensstadt 2.0 is a place of the future. The Berlin Senate has approved 9.9 million euros for the first research project "Electrical Drive…→Siemensstadt 2.0: Research and industry closely linked

-

Transfer – Stories

©Credit Silke Oßwald/FMP

Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview: Professor Dr. Volker Haucke, Director at the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP) and Professor of…→

©Credit Silke Oßwald/FMP

Transfer – StoriesBrain City interview: Professor Dr. Volker Haucke, Director at the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP) and Professor of…→In the balancing act between detail and overall concept

-

Transfer – Stories

© hj barraza/Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesOur guest author Dr Barbara Schäuble is Professor for Diversity-Conscious Approaches in the Theory and Practice of Social Work at ASH Berlin and a…→

© hj barraza/Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesOur guest author Dr Barbara Schäuble is Professor for Diversity-Conscious Approaches in the Theory and Practice of Social Work at ASH Berlin and a…→Guest contribution: A sudden change of course - classes moved online

-

Transfer – Stories

©DexLeChem

Transfer – StoriesLaunching a start-up while at university? Sonja Jost's success shows the way. Together with three fellow students, she founded DexLeChem after…→

©DexLeChem

Transfer – StoriesLaunching a start-up while at university? Sonja Jost's success shows the way. Together with three fellow students, she founded DexLeChem after…→"Bringing new knowledge to the market is very important to us"

-

Transfer – Stories

©Ivar Veermäe / Centre for Entrepreneurship

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Berlin is the German capital of start-ups. Many young companies have successfully been founded through Berlin and Brandenburg based…→

©Ivar Veermäe / Centre for Entrepreneurship

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Berlin is the German capital of start-ups. Many young companies have successfully been founded through Berlin and Brandenburg based…→"Society in particular benefits from high-tech start-ups" - university survey enters its third round

-

Transfer – Stories

©BIH|Thomas Rafalzyk

Transfer – StoriesAt the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) the main focus is on "translational research" - the transfer of findings from the research lab into clinical…→

©BIH|Thomas Rafalzyk

Transfer – StoriesAt the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) the main focus is on "translational research" - the transfer of findings from the research lab into clinical…→“There are now many great female scientists, achieving great things”

-

Transfer – Stories

©fotografixx - istockphoto.com

Transfer – StoriesIn the digital age learning behaviour changes profoundly. It is student-centered and technology rich. As a member of the Erasmus+ funded project…→

©fotografixx - istockphoto.com

Transfer – StoriesIn the digital age learning behaviour changes profoundly. It is student-centered and technology rich. As a member of the Erasmus+ funded project…→Exploring the future of learning

-

Transfer – Stories

© Brain City Berlin

Transfer – StoriesResearch results quickly and easily accessible online: The Open Access movement is campaigning for a paradigm shift in the field of publications and…→

© Brain City Berlin

Transfer – StoriesResearch results quickly and easily accessible online: The Open Access movement is campaigning for a paradigm shift in the field of publications and…→Open Access: free knowledge for everyone

-

Transfer – Stories

©ESCP EUROPE

Transfer – Stories29.10.2019 | Professor Andreas Kaplan is a Brain City Berlin ambassador and Rector of ESCP Europe Business School Berlin. The economist's research is…→

©ESCP EUROPE

Transfer – Stories29.10.2019 | Professor Andreas Kaplan is a Brain City Berlin ambassador and Rector of ESCP Europe Business School Berlin. The economist's research is…→"We have to be able to take everyone on the journey."

-

Transfer – Stories

Gudrun Piechotta-Henze

Transfer – StoriesIn time for the 2020/21 winter semester, ASH, the Alice Salomon University of Applied Sciences Berlin, is launching the first bachelor's degree to…→

Gudrun Piechotta-Henze

Transfer – StoriesIn time for the 2020/21 winter semester, ASH, the Alice Salomon University of Applied Sciences Berlin, is launching the first bachelor's degree to…→"We have to completely rethink nursing!" | 27.09.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

©Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin/Matthias Heyde

Transfer – StoriesThe courses offered by the HUWISU Summer University are varied and exciting, the target group is international: students from abroad who come to…→

©Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin/Matthias Heyde

Transfer – StoriesThe courses offered by the HUWISU Summer University are varied and exciting, the target group is international: students from abroad who come to…→When Berlin becomes one large seminar room ... | 15.08.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/d/csm_bwasihun-vdo_558x314_c0d384ce60.jpg) [Translate to English:]

Transfer – StoriesThe literary scholar Dr. Betiel Wasihun was traveling for science. After stops in Heidelberg, Yale, and Oxford, it brought her to Berlin two years…→

[Translate to English:]

Transfer – StoriesThe literary scholar Dr. Betiel Wasihun was traveling for science. After stops in Heidelberg, Yale, and Oxford, it brought her to Berlin two years…→“Berlin is a perfect location. Especially if you don’t want to pursue just a single avenue of scientific work.” | 12.08.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] Berlin University Alliance/Matthias Heyde [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/a/csm_Berlin_University_Alliance_Matthias_Heyde-558x314_4bc591ca3c.jpg) [Translate to English:] Berlin University Alliance/Matthias Heyde

Transfer – StoriesTogether we are stronger. And also more successful. As the "Berlin University Alliance," the Technische Universität Berlin, the Freie Universität…→

[Translate to English:] Berlin University Alliance/Matthias Heyde

Transfer – StoriesTogether we are stronger. And also more successful. As the "Berlin University Alliance," the Technische Universität Berlin, the Freie Universität…→Congratulations: The “Berlin University Alliance“ receives funding of the Excellence Strategy |19.07.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] David Ausserhofer/IGB [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/f/csm_Hupfer__Michael_____R__David_Ausserhofer_588x314_6fef164e57.jpg) [Translate to English:] David Ausserhofer/IGB

Transfer – StoriesBerlin is one of the most water-rich cities in Germany. But climate change does not stop at the Havel, Spree or Wannsee either. Dr. Michael Hupfer is…→

[Translate to English:] David Ausserhofer/IGB

Transfer – StoriesBerlin is one of the most water-rich cities in Germany. But climate change does not stop at the Havel, Spree or Wannsee either. Dr. Michael Hupfer is…→"We're trying to take a look into the future." | 04.07.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_helena-lopes-1338810-unsplash_558x314_857802ad2f.jpg) [Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesSend a digital lollipop or delicate fragrance notes via email or let the wind virtually blow against your face - research makes it possible. Learn…→

[Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash

Transfer – StoriesSend a digital lollipop or delicate fragrance notes via email or let the wind virtually blow against your face - research makes it possible. Learn…→Experiencing the digital world with all senses | 18.06.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] HZB/M. Setzpfandt [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/a/csm_LNDW_HZB_558x314_e1e3500ed5.jpg) [Translate to English:] HZB/M. Setzpfandt

Transfer – StoriesIn these times of fake news and pseudo-scientific publications, many people find it difficult to distinguish legitimate from dubious content. Only 54%…→

[Translate to English:] HZB/M. Setzpfandt

Transfer – StoriesIn these times of fake news and pseudo-scientific publications, many people find it difficult to distinguish legitimate from dubious content. Only 54%…→"Science needs to make us curious" | 11.06.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] Tim Landgraf [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/7/csm_Car2CarEnergySharing_Tim_Landgraf_558x314_485bf716e9.jpg) [Translate to English:] Tim Landgraf

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Berlin is considered one of the leading locations in Germany working on artificial intelligence. About 30% of all German AI companies are…→

[Translate to English:] Tim Landgraf

Transfer – StoriesBrain City Berlin is considered one of the leading locations in Germany working on artificial intelligence. About 30% of all German AI companies are…→Fish, bees, and self-driving cars | 07.06.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_Open-Access_Berlin-Partner_Wu__stenhagen_558x314_dd0c6e714d.jpg) [Translate to English:]

Transfer – StoriesScience and cultural heritage, freely accessible to everyone at any time on the Internet: The Open Access movement is promoting a paradigm shift in…→

[Translate to English:]

Transfer – StoriesScience and cultural heritage, freely accessible to everyone at any time on the Internet: The Open Access movement is promoting a paradigm shift in…→Knowledge for All - Open Access in Berlin | 28.03.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] Thomas Rosenthal - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/d/csm_Museum_fu___er_Naturkunde_Berlin_Thomas_Rosenthal_f11b8ba056.jpg) [Translate to English:] Thomas Rosenthal - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin

Transfer – Stories660 million euros in 10 years: The Natural History Museum Berlin - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin receives financial support for the further development…→

[Translate to English:] Thomas Rosenthal - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin

Transfer – Stories660 million euros in 10 years: The Natural History Museum Berlin - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin receives financial support for the further development…→Future of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin | 14.01.2019

-

Transfer – Stories

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/c/csm_TU_Berlin_Cem_Avsar_558x314_4b07bcb055.jpg) [Translate to English:]

Transfer – StoriesSpace exploration is experiencing a revolution thanks to commercialization by such companies as Elon Musk's SpaceX. But did you know that more facets…→

[Translate to English:]

Transfer – StoriesSpace exploration is experiencing a revolution thanks to commercialization by such companies as Elon Musk's SpaceX. But did you know that more facets…→From Berlin to the moon: the space industry is booming in Berlin | 03.09.2018