-

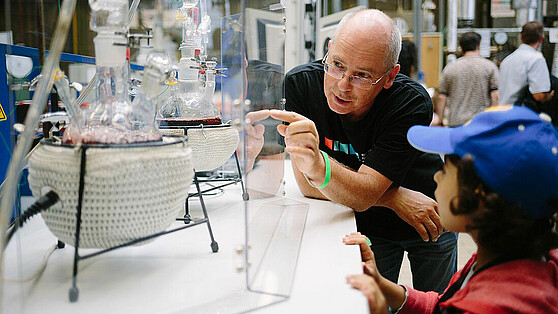

(From left to right) Steffen Terberl/FU Berlin; Prof. Dr. Hannes Rothe/ICN Business School, photo: Ernestine von der Osten-Sacken

16.12.2021“BioTech does not get up and running on its own”

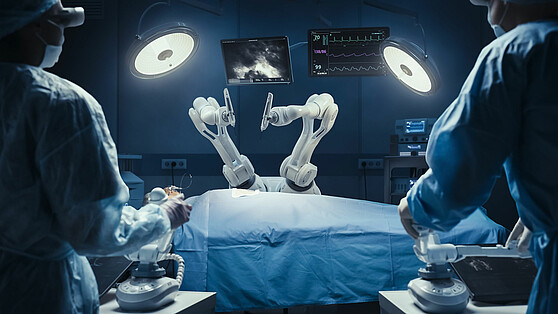

Brain City Berlin is one of the top locations in the health industry worldwide. However, in the BioTech sector, the region is not making full use of its innovation potential. At the same time, Berlin has a good chance of catching up with top clusters such as Cambridge or Boston. This is the conclusion of the “Deep Tech Futures Report 2021: Bio and HealthTech Startups in Berlin”

The study, which was led by Prof. Dr. Hannes Rothe, Associate Professor at the ICN Business School Berlin and co-founder of the Digital Innovation Hub of the Freie Universität Berlin (FU Berlin), compares Berlin with Cambridgeshire (Great Britain) and other locations in Germany on the basis of workshops, quantitative data analyses and interviews with founders, scientists, investors and technology transfer institutions, infrastructure providers and large companies.

Prof. Dr. Hannes Rothe and Steffen Terberl, Head of the start-up service of the FU Berlin, Profund Innovation, tell us in an interview more about the results of the report, the opportunities of Berlin as a location and how they could be used.

Dr. Rothe, for the recently published “Deep Tech Futures Report 20121” you focused on Bio and HealthTech start-ups. What was the trigger for doing the study?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: As a business computer science specialist with a focus on entrepreneurship, I have been involved with the BioTech sector since 2018. I found it unbelievable that there is a high concentration of large BioTech and HealthTech companies in other regions, but not in Berlin. Berlin is a great research location: We have three universities here alone that teach and research in the fields of natural sciences and technology, and with the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, we have the largest university hospital in Europe. Large research institutions such as the Max Delbrück Centre for Molecular Medicine (MDC) or the Max Planck Society (MPI) are also located here. But if you look at the start-up scene here, you will look in vain for large Health and BioTech start-ups – apart from Digital Health start-ups. We wanted to know how Berlin is positioned compared to other regions – and what can be done better if necessary.

Steffen Terberl: The planned technology and start-up centre FUBIC in Berlin-Dahlem should be completed in 2025. We will then also have a large proportion of laboratory space here. That was a reason for Profund Innovation to deal more closely with the topic of start-ups in the life sciences area.

An essential conclusion of the study “Bio and HealthTech Start-ups in Berlin” states: As an ecosystem for Bio and HealthTech start-ups, Berlin is not making full use of its potential. What does that mean exactly?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: When we refer to start-ups in Berlin, we usually mean digital start-ups. They are the Zalandos, the Rocket Internet and app developers in the field of digital health like Ada, but not like start-ups in biotechnology, diagnostics or medical technology. Such start-ups are here, but they are not the focus of investors. Berlin is the leader in Germany for Bio and HealthTech. Basic research is way ahead here anyway. As far as start-ups are concerned, there is still some potential in the capital region compared to top international clusters such as Cambridge or Boston.

Why is that?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: This is mainly due to the long development times of Bio and HealthTech products. And the new technologies still have to be brought onto the market. A health app, on the other hand, can be written within a few months. It then “only” has to be certified. So the process is much shorter. It also requires significantly less investment. For start-ups in the Bio and HealthTech sector, you need specific know-how and a completely different network. The requirements that founders face in this area therefore differ significantly.

Are there any other core issues?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: One of the key problems that we also identify in the study is: Although there are many Bio and HealthTech start-ups in Berlin, these usually remain small. This creates a scaling problem. This is a problem because no cycle can be built up. A start-up ecosystem works like this: As a start-up grows, it hires employees. Then, at best, it will be successful and sold. But the employees do not move away. Rather, they stay in the region and start something new. Successful ecosystems therefore feed themselves. Such an ecosystem already exists in Berlin in the digital sector – but that is not even remotely the case in the BioTech sector.

In the study you also mention a scaling problem...

Dr. Hannes Rothe: Yes, that’s right. We leave these companies in Berlin as small ones. We do not help them to grow. There are some resources, but ultimately a lot of that capacity is very distributed and not well connected. One reason for this is certainly: BioTech start-ups have so far received little attention because other areas have been more successful. This has changed with Corona. A company like Biontech, which in the meantime is making a substantial contribution to the German gross domestic product, can achieve a lot. There has certainly been a change. In Berlin, however, a lot of potential from basic research continues to be poorly transferred into growing start-ups.

Why is that so – isn’t Berlin generally committed to a well-functioning transfer of knowledge in the economy?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: Scientists who do research in the region tend to be too young and inexperienced. They are younger than in Boston and more inexperienced than in Cambridge. They do their doctorate and then start a business. They have no industry experience, no network and they do not know how to develop a medical product. Rather, they learn how to develop a medical product on-the-job. This is a problem because it takes a long time to develop such a product or diagnostic tool. There are many hurdles to be overcome. Whoever does not know these hurdles from the beginning, has to do some things twice – and that delays the process even more.

Basically, doesn’t that also apply to other areas?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: Yes, but it is especially serious in the health sector because it is so heavily regulated. Logically, a lot of attention is paid to safety. If it is found in phase two that something was not done right in phase one, you have to go back. If that is the case, 500,000 Euro can quickly be used up. And an investor may not be prepared to go through that twice. That is why, right from the start, start-ups in Boston or in Cambridge are provided with managers who have been through the process before,

That also exists in Berlin. Doesn’t the “Science & Startups” network, for example, comprise around 1,700 mentors? Is there a lack of experts here who can provide the support you mentioned?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: Yes to both of them. First of all, these experts are not co-founders, rather they are “only” mentors. This means that they are not an active part of the team, but only give their opinion. And secondly, there is a lack of people in Berlin who can provide this support because there are still no unicorns in Berlin’s Bio and HealthTech ecosystem. We do not have any billion dollar companies here that have already successfully gone through the process once or twice. Accordingly, there are fewer people in the capital region who can share this experience.

In the study you compare Cambridgeshire in Great Britain as a best practice example. What does Cambridge do differently than Berlin?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: Cambridge actually started ten years before Berlin - there is a very good book on it, “The Cambridge Phenomenon”. Cambridge went through a process similar to that of Berlin or Silicon Valley in the 1970s. The location initially started with information technology. At some point the hardware and software founders also invested outside their field. In the 1980s and early 1990s, Cambridge began investing in BioTech and HealthTech. We only started that in the 2000s. In that regard, there were large BioTech and HealthTech companies in Cambridge much earlier than here, which have now grown into unicorns. Other big players followed suit. Today Cambridge is THE leading BioTech cluster in Europe. AstraZeneca officially relocated its headquarters to Cambridge just a few weeks ago – because there is the aforementioned start-up ecosystem and cutting-edge research there – and because the company can set up joint labs there.

The study provides recommendations based on the comparison with Cambridge. This applies to addressing investors, for example.

Dr. Hannes Rothe: Precisely. Investors working in Cambridge do not invest in one, but in several start-ups. They know the ecosystem there. And they have an interest in ensuring that it lives and lasts. They are predominantly regional investors – but even international investors finance several start-ups there. This leads to these start-ups having more support. The exchange of information between the founders is also more intensive and the ecosystem tends to be promoted more strongly than in Berlin. Public sponsors are particularly active here. This is very important because in the Bio and HealthTech sector a long period of time has to be financed. But the process takes much longer than in Cambridge, for example, because there is a lack of private capital and because few help BioTech and HealthTech start-ups in a targeted way to raise private capital. As a result, our start-ups are usually dependent on public money for a very long time.

What could help the local start-ups?

Dr. Hannes Rothe: It is necessary, and this is also one of the core recommendations of the study, to build a platform that links the local industry more closely with the research-related incubators and the science parks of the city. Such a platform could also be used to find private regional investors who can support the start-ups with financed professionals. In principle, the chances for such a platform and therefore a boost for Bio and HealthTech start-ups in Berlin are good, because the leading local scientific institutions cooperate very intensively and are attaching increasing importance to the transfer of research results into practice.

Steffen Terberl: There is now also a blueprint for such a platform: the K.I.E.Z. - Artificial Intelligence Entrepreneurship Centre for the promotion of start-ups in the AI field, which was launched in September. In principle, we are doing exactly what we recommend as a model project for the BioTech area: We have very special services there. We are looking for investors who want to enter this area specifically, for talents and the right mentors. Individual institutions such as Profund Innovation cannot do this alone. We are all not big enough for that and we do not have the critical mass. But of course together it makes sense.

Dr. Hannes Rothe: There is another big difference between the BioTech ecosystems in Berlin and Cambridge: Our start-ups hold significantly fewer patents. One of the reasons for this is that the technology transfer that we are currently operating in the capital region is heavily focused on licenses. This means that the universities issue patents and ideally license fees then flow back to the universities. In Cambridge, the ideas belong to the founding companies, which, when they have grown enough, can stimulate further ideas. Start-ups develop further patents there after they have founded, and these also belong to them. This is usually not the case here. The problem is more likely to be accepted.

Steffen Terberl: However, this policy is justified. Universities cannot simply give away their intellectual property. At the moment, it only makes sense if investors get into the process early on and buy ideas out of the university on market terms. A start-up should be able to take care of patent management itself. The way the start-ups are currently positioned here at the universities, it is more positive for them if the respective university takes care of the patent management.

What tip would you give young teams that want to set up from within the university?

Steffen Terberl: We generally recommend that our start-ups focus on the market and potential customers relatively early on. Traditionally, scientists like to stay longer at the university. It is therefore important to integrate the business component into the team at an early stage. Normally, very homogeneous teams come to us that have developed out of a working group. Most of the time, they completely lack business understanding initially. One of our concerns is to bring this component in as quickly as possible.

Dr. Hannes Rothe: There are courses for science-based start-ups that life science students can also make use of. These help first of all to develop a basic understanding of what it means to found a start-up. It is also about learning to understand the language of business. In addition, there is now a Berlin Startup Scholarship programme for the health industry. This is a small amount of money, but a good way to get going in a start-up. In addition, it is of course important to get in touch with the incubators. However, the problem with the lack of proximity to industry remains. At the moment, everyone has to be very active themselves. BioTech unfortunately does not get up and running on its own.

The research group and partner institutions are planning a joint event on the report in spring 2022. More information about the email distribution list: https://mailchi.mp/1402c91c5174/towards-bio-futures-berlin

- „Deep Tech Futures Report 2021: Bio- und HealthTech Startups in Berlin“ (Infos und Download, German only)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/d/csm_bwasihun-vdo_558x314_c0d384ce60.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Berlin University Alliance/Matthias Heyde [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/a/csm_Berlin_University_Alliance_Matthias_Heyde-558x314_4bc591ca3c.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] David Ausserhofer/IGB [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/f/csm_Hupfer__Michael_____R__David_Ausserhofer_588x314_6fef164e57.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_helena-lopes-1338810-unsplash_558x314_857802ad2f.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] HZB/M. Setzpfandt [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/a/csm_LNDW_HZB_558x314_e1e3500ed5.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Tim Landgraf [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/7/csm_Car2CarEnergySharing_Tim_Landgraf_558x314_485bf716e9.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_Open-Access_Berlin-Partner_Wu__stenhagen_558x314_dd0c6e714d.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Thomas Rosenthal - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/d/csm_Museum_fu___er_Naturkunde_Berlin_Thomas_Rosenthal_f11b8ba056.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/c/csm_TU_Berlin_Cem_Avsar_558x314_4b07bcb055.jpg)