-

©DexLeChem

09.04.2020"Bringing new knowledge to the market is very important to us"

Launching a start-up while at university? Sonja Jost's success shows the way. Together with three fellow students, she founded DexLeChem after graduating from TU Berlin in 2013 with degrees in industrial engineering and technical chemistry. The high-tech company based in the Wuhlheide Innovation Park offers innovative production improvements in the area of green chemistry.

Ms. Jost, what motivated you to take the plunge and launch a company right out of university?

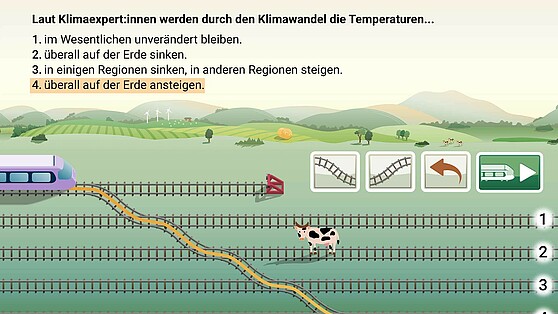

I want to change things. When I see that it's possible to produce things more ecologically while saving costs, I'm not going to sit back and relax. I'm not the type to wait. Germany is the fourth largest producer of chemicals in the world, so we also have an obligation. We didn't have “Fridays for the Future” back in 2013, but developments such as climate change were clearly foreseeable. I am a child of the 1980s and I paid attention to the big environmental movements back then. And although I have always been interested in industry and production, [going green] has had a huge impact on my mind set. I'm not someone who holds on to the impossible, but I thought to myself: I never want to blame myself for not giving it a try!

DexLeChem emerged from TU Berlin as a start-up.

Exactly, we are a spin-off from the UniCat Cluster of Excellence at TU Berlin. At that time, I developed a process for producing complex chemicals in water instead of petroleum-based organic solvents. This had not previously been possible, because you had to use certain complex, homogeneous catalysts that could not be used in water. It was this process that laid the foundation for DexLeChem's business concept. What's special about it is that it can be used to manufacture fine chemicals for the pharmaceuticals industry in an environmentally and resource-friendly manner.

It is particularly difficult for scientific companies to launch on the market. How did this work out for you?

Many start-ups are launched each year in the German start-up capital Berlin, but only a few that work in the natural sciences for industry. In the first year, we were still able to use the facilities at the TU Berlin. “We were really lucky. Berlin was already the German leader for securing financing. There are many research projects running at universities and research institutions. Of course, it is difficult to get space to try out a start-up idea. Back then, we only made it because two professors supported us. Later, IHK Berlin financed a laboratory container for scientific start-ups: the INKULAB provides free laboratory workspace. We co-initiated the project.

You also received an EXIST grant, right?

Yes. In order to receive an EXIST grant, the university had to agree up front that it would provide the facilities. The infrastructure is a prerequisite for getting the funding. We were very lucky to be included in the EXIST research transfer. This is the big brother of the start-up grant, so to speak. Very few teams receive this funding. Every year there are around 30 projects across Germany. When a chemistry start-up makes the cut, that's a big deal. It also shows that there is a high demand in this area.

In the meantime, you have established yourself in the market. Not every start-up team can say that. What was your recipe for success?

It took us almost a year and a half to get the first customer. It's almost like a game in industry. Nobody wants to be the first. We had to nibble away at the resistance. They'd keep on saying: "Come back when you have a customer." In the end, our first customer was a Swiss company. We first made contact with them at a trade fair. A cornerstone of our success was that we expanded our business model to include services and products for which we did not have a unique selling proposition but were nevertheless very good at. We started by developing water-based chemical processes for industry, which can be used to reuse expensive catalysts in pharmaceuticals production. We now offer a much broader range of services. We recognised that project initiation takes a long time in industry and thought about those services we could also offer in order to generate more sales.

Such as?

There is a need in industry for teams that work on digitalising production in the broadest sense. In the development of our water-based processes, we use many modelling tools including quantum chemical simulations, dynamic process simulations, and various big data methods. We now offer these services as well as general services in the field of green chemistry, i.e. sustainable solutions for use in industrial processes. The expansion of our range of services brought the breakthrough we needed because it pushed more orders into the pipeline. We were then able to convince industrial companies that they were not taking too great a risk with us. This is because we made our development process transparent and could show that we have everything under control.

For four years, DexLeChem was located in Bayer's incubator, the CoLaborator. How did you benefit from this?

The time at Bayer was extremely helpful because we had access to the infrastructure there and didn't have to set up our own lab. Moving from the university to Bayer also meant another step towards independence. Overall, we went through a gradual, cushioned process. At the end of 2018, we moved to the Wuhlheide Innovation Park and here we really do everything ourselves. I don't think we could have done everything on our own from the start. Nobody tells you what to look out for.

And to what extent did Bayer benefit from you?

The proximity to a start-up brings new perspectives into a company. The topic of intrapreneurship is now very important in industry. At the time, we were the only chemical start-up in the CoLaborator and gave lectures to our colleagues there. As one of the first chemical start-ups in Germany, we also worked early on to help establish the start-up scene in this field. Bayer naturally benefited from this as well.

You are still one of the few women in the management of a German start-up. Is this also unusual for young scientific companies?

There aren't as few women in the chemical start-up scene as you might think. Surveys speak of 25 to 40%. This is because there is generally a high proportion of women in the chemical, biology, and pharmaceutical sectors. Depending on the field, this ranges between 38 and over 50%. Of course, there are therefore more women in these fields who are in a position to found a start-up. The start-up scene with its media presence that originated in the dot-com bubble at the time is certainly IT-dominated. And that's traditionally an area with a low proportion of women. It is different in other countries. In Iran, for example, women make up about 50% of IT students. However, the world of fund managers is very testosterone-driven. Women clearly get less capital, even though their companies perform better. This is, of course, a huge problem for funds owners because they generate less returns.

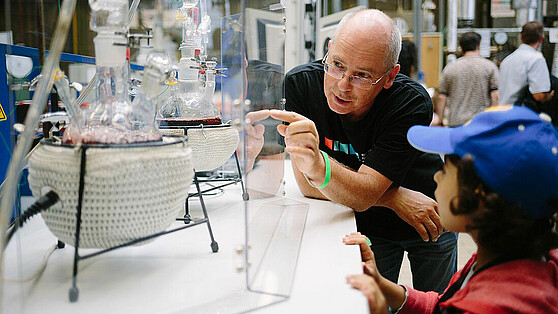

The science scene in Brain City Berlin is considered to be very well networked. How do you make use of this?

The proximity to science in Berlin is very important to us. We are still working closely with the Cluster of Excellence at TU Berlin. There have also been close connections with professors at the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin and Freie Universität Berlin. Bringing new knowledge from science to the market is very important to us. We are therefore always open to cooperation. That is the nice thing about Berlin: we have outstanding science and a great scientific start-up scene. The mix here works well!

To what extent is DexLeChem committed to supporting scientific start-ups in Berlin?

We founded DexLeChem seven years ago, which has helped us to build and network the start-up scene for many years. In this respect, I have found good friends here among entrepreneurs. We help each other with content when they run into technical problems. Until September 2019, I was also on the board of the Federal Association of German Start-Ups. I am always being invited by universities all over Europe to give lectures. I do a lot to support founders in the natural sciences.

Can you provide any specific examples?

The Lab2Venture, for example, a hands-on and experimental laboratory at the Freie Universität zu Berlin. There we accompanied a school class for a year. As part of a project, the students went through what it is like to launch a start-up in the chemical sector. We still work with TU Berlin, the Centre for Entrepreneurship and the B!GRÜNDET Network of the Berlin universities and the Berlin University Alliance. This goes far beyond the topic of start-ups: for the Berlin University Alliance, for example, we were looking for raw materials to produce disinfectants as part of measures to prevent the further spread of the coronavirus. There's a lot going on at Berlin's universities.

Speaking of which, do you have any tips for young researchers who want to start their own businesses?

First of all: the problems are always the same. Many are standing in front of a mountain and don't know how to tackle it. My tip would be to write to companies that have been on the market for a few years and ask if they could possibly give tips. For example, DexLeChem. We love helping those in the chemical sector. However, there are now many successful entrepreneurs in the natural sciences.

In 2017, you were recognised by the online magazine Edition F as one of "25 women who are changing the world." Do you still want that?

Definitely! Almost everyone who launches a start-up in the natural sciences wants to build something sustainable. You're not looking for a quick exit.

Last question: if you could wish for something, what would it be?

I would like to have capital to build a sustainable chemical company. At the end of 2019, we founded a production company because we want to manufacture sustainable pharmaceutical ingredients and intermediates ourselves. We are currently looking for partners for this. We believe that the time has come to bring production back to Germany and thus secure our supply chain. (vdo)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/d/csm_bwasihun-vdo_558x314_c0d384ce60.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Berlin University Alliance/Matthias Heyde [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/a/csm_Berlin_University_Alliance_Matthias_Heyde-558x314_4bc591ca3c.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] David Ausserhofer/IGB [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/f/csm_Hupfer__Michael_____R__David_Ausserhofer_588x314_6fef164e57.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Helena Lopes / Unsplash [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_helena-lopes-1338810-unsplash_558x314_857802ad2f.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] HZB/M. Setzpfandt [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/a/csm_LNDW_HZB_558x314_e1e3500ed5.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Tim Landgraf [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/7/csm_Car2CarEnergySharing_Tim_Landgraf_558x314_485bf716e9.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/6/csm_Open-Access_Berlin-Partner_Wu__stenhagen_558x314_dd0c6e714d.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Thomas Rosenthal - Museum für Naturkunde Berlin [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/d/csm_Museum_fu___er_Naturkunde_Berlin_Thomas_Rosenthal_f11b8ba056.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/c/csm_TU_Berlin_Cem_Avsar_558x314_4b07bcb055.jpg)